Introduction- Iron:

Iron, a humble element nestled in the periodic table’s Group 8, boasts a tale as thrilling as any treasure map. This “abandoned metal,” as Carl Sagan aptly described it, forms the backbone of steel, fuels life’s oxygen cycle in our blood, and whispers tales of empires forged and wars won. Its journey, from meteoric whispers to civilization’s cornerstone, is an epic saga of human ingenuity and its transformative impact on the world. The invention of iron marked a significant shift in human technology and innovation and has played a crucial role in the development of human civilizations.

Iron is a grey-colored metal ductile, malleable and a good conductor of heat and electricity. It can attract magnets and can be magnetized. Iron is believed to be the most abandoned material in the universe making 5 % of Earth’s crust, and it can be extracted from iron ore through smelting. Smelting involves heating the iron ore with a chemical-reducing agent in a furnace, removing other impurities left as gas or slug leaving a pure metal base behind which removes the impurities. The fossil fuel sources of carbon such as coke or in earlier times charcoal are used as a chemical reducing agent.

Invention of Iron-

The discovery and first use of iron for things like the tip of spears, daggers, and ornaments by humans can be traced back to ancient civilizations around 4000 BCE in the Middle East. Turkey

and Iran. The time period of the discovery of iron and its use of iron by humans can be divided into three main periods: the prehistoric period, the Iron Age, and the modern era.

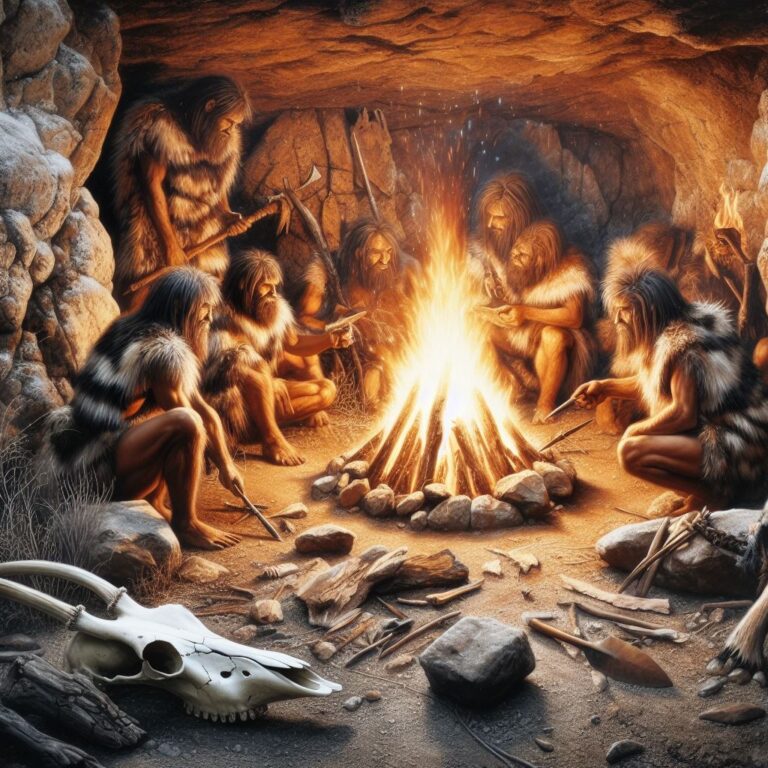

In the prehistoric period, from the beginning of human civilization after the Neolithic revolution until roughly 1200 BCE, humans started using stone tools and weapons. During this period, humans were hunter-gatherers (before the Neolithic revolution), and as the technology was limited they could only crate tools using natural materials such as rocks, bones, and wood. During the same time, the use of meteoric iron can be found, for example, a dagger made of meteoric iron found in the tomb of Tutankhamun contains similar properties and composition (of iron, nickel and cobalt) to meteorites.

Research shows that during this period humans first time discovered iron ore, as iron deposits are often found in the same locations where copper and other metals were used for tools and weapons. However, till then it was difficult to extract iron from its ore, and the technology for smelting iron did not exist at that time.

The Iron Age Emerges

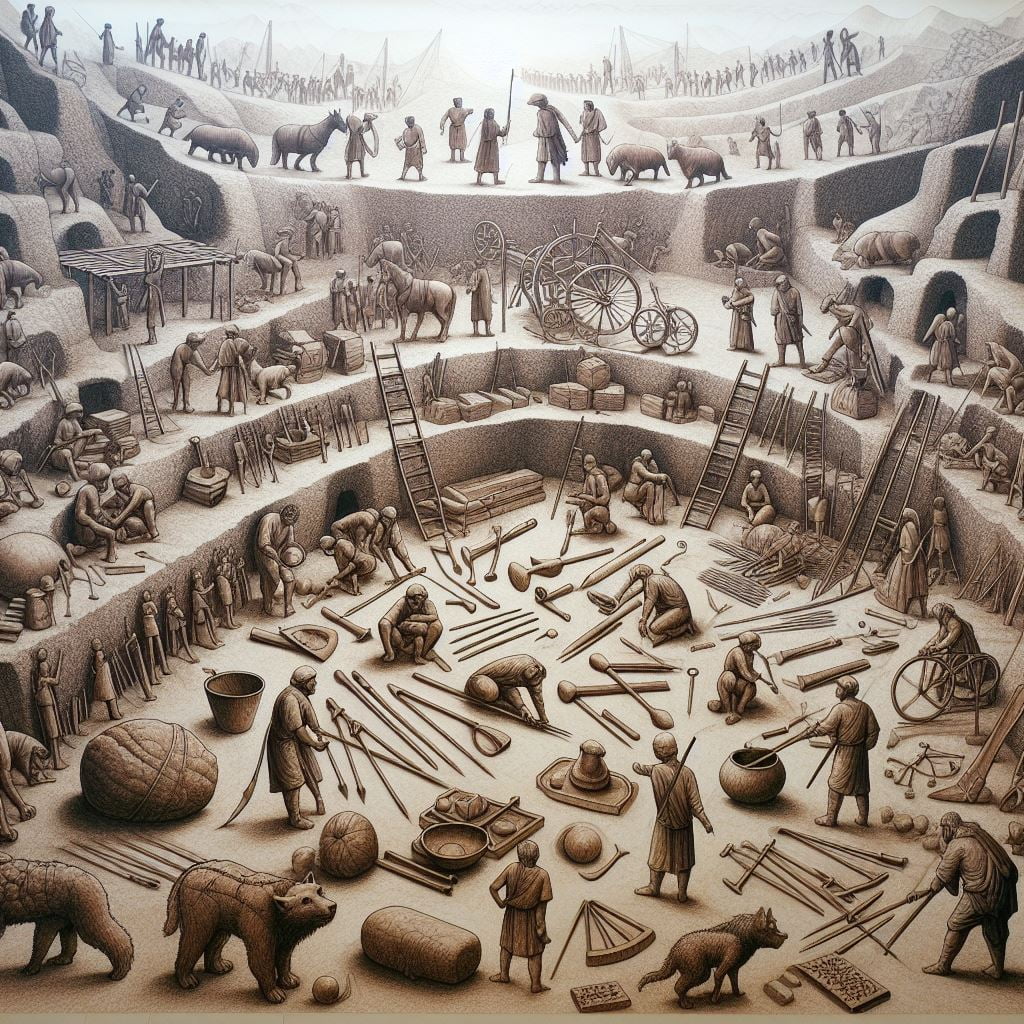

After the Stone and Bronze Age, the Iron Age started around 1200 BCE when people in the Middle East developed the technology to extract iron from its ore. Samples of smelted iron have been found in Mesopotamia and Syria. Smelting is the process of extracting desired metal from ore with the help of heat and chemical reducing agents, Hittites established their empire in Anatolia and began the first iron production from its ore. During the period use of iron was widespread for tools and weapons, and it played a very important role in the development of ancient civilizations like the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians.

- Bronze Age limitations: While bronze dominated prior to the Iron Age, its limitations became apparent. Bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, was expensive to produce and relatively soft, especially compared to desired weapon qualities.

- Iron ore’s potential: Humans had encountered iron ore for millennia, but extracting and shaping it required higher temperatures than bronze smelting. Around 1800 BCE, technological advancements, like improved furnace designs and the use of bellows for increased air supply, paved the way for manipulating iron’s potential.

During the Iron Age, iron was mainly used to make war weapons like armor, swords, spears, and arrows. The properties of Iron weapons were stronger tougher and more durable compared to weapons made from bronze or copper and it gave armies a significant advantage in warfare. with these qualities, iron was also used to make tools for farming, construction, and other activities, which helped to increase productivity and improve the standard of living for many people.

During the Industrial Revolution, which began in the 18th century, a major expansion in the use of iron and its alloys. Below are some important alloys:

Alloys of Iron

Pig iron:

- Carbon Content: 4-5% (High)

- Impurities: High levels of sulfur, silicon, phosphorus (brittle and weak)

- Properties: Hard, brittle, not malleable (cannot be shaped by hammering), high melting point.

Applications: Not directly usable in most applications. Primarily used as a raw material for steel production.

Cast iron:

- Carbon Content: 2-4%

- Silicon Content: 1-6% (Significant)

- Other Elements: Trace amounts of manganese

- Types: White cast iron (high silicon) and Gray cast iron (lower silicon with flakes of graphite, making it less brittle).

- Properties: Hard, brittle (white cast iron), relatively strong in compression (resists crushing), good wear resistance.

- Applications: Engine blocks, cookware, pipes, decorative pieces (white cast iron).

Carbon steel:

- Carbon Content: 0.4-1.5%

- Other Elements: Trace amounts of manganese, sulfur, phosphorus, and silicon.

- Properties: Varies depending on carbon content. Lower carbon steels are more ductile (can be shaped by drawing) and weldable. Higher carbon steels are harder and stronger.

- Applications: A broad category encompassing many types of steel used in construction (beams, rebar), tools (wrenches, screwdrivers), machinery parts, and vehicles.

Wrought iron:

- Carbon Content: Less than 0.2% (Very Low)

- Properties: Malleable (easily shaped by hammering), ductile (can be drawn into wire), welds well, resists corrosion. Softer and less strong than steel.

- Applications: Historically used for decorative ironwork (fences, railings), chains, nails. Largely replaced by steel in modern applications.

Alloy steels:

- Carbon Content: Varies depending on the desired properties.

- Alloying Elements: Chromium, vanadium, molybdenum, nickel, and tungsten are commonly added in various combinations.

- Properties: Alloying elements significantly improve various properties of steel, such as strength, hardness, corrosion resistance, and heat resistance.

- Applications: A very broad category encompassing a wide range of steels designed for specific purposes. Examples include stainless steel (corrosion resistant), tool steel (holds an edge), and high-strength steel (used in bridges and buildings).

The cost of steel production increases with the amount of alloying elements used. Therefore, alloy steels are typically used only when their specific properties are essential for the application.

The terms “mild steel” and “low-carbon steel” are often used interchangeably and refer to steels with a carbon content below 0.3%. These steels are widely used due to their good balance of properties and affordability.

These are the some of important alloys of iron. Considering their mechanical properties iron and its alloys are used to make things like steam engines, locomotives, and other machinery that powered the factories and mills. Iron was also used to build bridges, buildings, and other structures, which started the Industrial Revolution and enabled the growth of modern cities.

Timeline- History of Iron

A timeline of the discovery of iron and its use throughout human history:

4000 BCE: The Birth of Iron Pigments in Mesopotamia

Around 4000 BCE, in the cradle of civilization that was Mesopotamia, a fascinating development was unfolding. Humans, seeking to add more beauty and utility to their lives, discovered the potential of iron-containing minerals as pigments for their pottery. This artistic endeavor marked the earliest known interaction between humanity and iron, long before its transformative potential in tools and weapons was fully realized.

Archaeological excavations at sites like Tell Tello and Nippur have yielded a treasure trove of these iron-painted pottery fragments. Recent discoveries, like the intricate black-on-red designs on bowls unearthed at Tell Chuera, showcase the sophistication and artistic flair of these early pigment masters.

Chemical analyses of these Mesopotamian ceramics reveal a fascinating palette. Ochre-reds and deep browns whispered of hematite, while the enigmatic black glazes likely owed their existence to magnetite. These weren’t mere decorative flourishes; they were testaments to an early understanding of mineral properties and their interaction with fire.

3000 BCE: Heralding the Hittites and Iron Tools in Turkey

The Hittites, an ancient civilization nestled in what is modern-day Turkey, stepped onto the stage of history around 3000 BCE. They were among the pioneers who harnessed the remarkable qualities of iron for a more pragmatic purpose – crafting tools and weapons. Their journey with iron was a significant stride towards the Iron Age, paving the way for innovations yet to come.

Long before the Hittites rose to prominence, iron’s whispers echoed through Anatolia. Archaeological evidence from sites like Alaca Höyük and Arslantepe reveals tantalizing trinkets – iron beads and ornaments dating back to 4000 BCE. These weren’t mere accidents; they showcase early curiosity and experimentation with this enigmatic metal. Studies by Begeyen et al. (2015) suggest these Anatolian artisans possessed a nascent understanding of iron’s unique properties, potentially even utilizing meteoric iron fragments for their creations.

While early Anatolian civilizations laid the groundwork, the Hittites, around 1200 BCE, refined the craft. Their efficient smelting techniques, utilizing bellows for increased air control and improved furnace designs, enabled them to produce iron on a larger scale and of higher quality. This mastery, documented in texts like the Iron Tablets of Nippur, translated into formidable weaponry like swords and spearheads, giving the Hittite empire a decisive edge and solidifying their reputation as iron pioneers.

Article: Begeyen et al., 2015, “Early evidence for meteoritic iron use in the Near East and southeastern Anatolia”

1200 BCE: The Iron Age Dawns in the Middle East

Around 1500 BCE, the embers of the Iron Age began to glow in the Middle East. Bronze, the dominant metal of the era, had reached its limitations, proving costly and relatively soft. But ingenuity ignited a solution. Archaeological whispers from sites like Tell Hamidi and Tel Tabriya reveal advancements in furnace technology, with the adoption of bellows and improved designs allowing for higher temperatures. These innovations unlocked the key to iron’s potential, laying the groundwork for its extraction and manipulation.

While the technological stage was set, the Hittites emerged as the conductors of this transformative symphony. In Anatolia, around 1200 BCE, their mastery of ironworking techniques revolutionized the landscape. Efficient smelting processes, utilizing charcoal as a fuel source and achieving higher furnace temperatures, allowed them to produce iron on a larger scale and of remarkable quality. Evidence of their pioneering spirit can be found in the iron tools and weapons unearthed at sites like Hattusha and Gordion, showcasing their superior strength and durability compared to their bronze counterparts.

The Iron Age story continues to evolve. Recent excavations in sites like Arslantepe and Beyköy have pushed back the timeline of intentional iron smelting even further, suggesting a more gradual transition from bronze to iron.

Article: “Iron Age”

800 BCE: The Iron Age Spreads Across Europe

While 800 BCE marks a symbolic milestone, the Iron Age’s arrival in Europe wasn’t a single dramatic event. It was a gradual migration, beginning around 1200 BCE with cultural exchange and trade networks carrying whispers of ironworking techniques from Anatolia and the Middle East.

- Hallstatt Culture (800-450 BCE): In Central Europe, the Hallstatt culture embraced iron, crafting sophisticated tools, weapons like swords and daggers, and even intricate jewelry showcasing their skilled metalworking. Studies suggest they developed their own smelting techniques, adapting Anatolian knowledge to local resources like bog iron.

- Villanovan Culture (800-500 BCE): In Italy, the Villanovan culture also adopted iron, utilizing it for tools and weapons but also for cremation urns and other ritualistic objects. Archaeological evidence reveals their own unique furnace designs, highlighting the decentralized nature of technological advancements.

- Iberian Iron Age (800-200 BCE): The Iberian Peninsula saw a distinct trajectory, with iron appearing earlier (around 850 BCE) and playing a significant role in agriculture and everyday life alongside weapons. Studies suggest cultural exchange with the Phoenicians influenced their ironworking practices.

The Iron Age wasn’t just about sharper swords and sturdier tools. Ironworking fueled economic growth, leading to the emergence of specialized artisans and trade networks. Social structures evolved, with skilled metalworkers gaining prominence. This era also witnessed significant advancements in agriculture, construction, and even artistic expression, with iron ornaments and decorative objects becoming prevalent.

700 BCE: Assyrians Forge an Empire with Iron

The Assyrians, masters of warfare and empire-building, stand as a powerful testament to iron’s strategic advantage. Around 700 BCE, their armies, equipped with superior iron weapons and armor, dominated the battlefield. Studies suggest their innovative use of chariots, combined with iron weaponry, created an unstoppable force that reshaped the political landscape of the Middle East.

While the Assyrians showcased the transformative power of iron in warfare, its impact wasn’t limited to them. From the Greeks utilizing iron hoplites to the Celts wielding iron swords, this transformative metal redefined military strategies and tactics across Europe and beyond.

By weaving together evidence from archaeological finds, regional variations, and the impact on various aspects of life, this revised narrative offers a more in-depth and nuanced picture of the Iron Age’s spread across Europe. It moves beyond a mere timeline to capture the intricate tapestry of innovation, adaptation, and societal transformation that unfolded as iron forged its way across the continent.

600 BCE: Persia’s Iron Age Flourishes

While 600 BCE marks a symbolic peak, Persia’s Iron Age wasn’t merely a static monument; it was a vibrant era of innovation and adaptation. Iron wasn’t just about swords and spears; it became the backbone of Persian civilization, shaping its architecture, everyday life, and even its identity.

- Architectural Marvels: Studies of iconic structures like the Apadana at Persepolis reveal the extensive use of iron in beams, nails, and decorative elements. Its strength and durability allowed for grander architectural feats, defying gravity and showcasing the empire’s engineering prowess.

- Beyond Grandeur: Iron in Everyday Life: Archaeological evidence from sites like Susa and Pasargadae paints a picture of widespread iron usage in tools for agriculture, construction, and domestic activities. Studies suggest iron sickles and hoes increased agricultural productivity, while iron cooking utensils and household implements transformed daily life.

- Artistic Expression: Iron wasn’t solely utilitarian; it found its way into artistic expression as well. Jewelry, decorative objects, and even weapons were adorned with intricate ironwork, showcasing the skill and artistry of Persian metalworkers.

500 BCE: Iron Takes a Backseat

Attributing a “decline” to iron around 500 BCE would be an oversimplification. The Iron Age didn’t vanish; it evolved. While the dominance of iron may have waned, it wasn’t replaced but rather complemented by other materials.

- Bronze’s Enduring Charm: Studies suggest bronze continues to be valued for its aesthetic qualities and specific applications like ritualistic objects and high-precision tools. The coexistence of iron and bronze highlights the nuanced interplay of factors influencing material usage.

- Steel’s Rise to Prominence: The development of steel, an alloy of iron and carbon, offered superior strength and flexibility. While evidence suggests widespread steel adoption took centuries, its emergence marked a technological advancement within the ironworking domain, not a replacement of iron entirely.

300 BCE: China’s Qin Dynasty Masters Iron

While Persia’s Iron Age flourished in the West, a parallel narrative unfolded in the East. The Qin Dynasty, established around 300 BCE, embraced iron wholeheartedly, recognizing its transformative potential.

- Military Might: Iron weapons and armor played a crucial role in the Qin’s military prowess, contributing to their unification of China. Studies suggest advancements in ironworking techniques fueled the mass production of standardized weaponry, giving the Qin a decisive edge.

- Agricultural Revolution: Iron tools dramatically improved agricultural efficiency. Studies estimate iron plowshares increased land productivity by 50%, contributing to food security and population growth, and laying the foundation for China’s economic and military strength.

- Infrastructure Development: The Qin Dynasty utilized iron for large-scale infrastructure projects like the Great Wall of China. Its durability and strength made it ideal for construction, solidifying the empire’s territorial control and communication networks.

300 CE: India’s Gupta Empire and Iron’s Versatility

While 300 CE marks a symbolic peak, the Gupta Empire’s relationship with iron was intricately woven into the fabric of Indian society for centuries prior. Studies suggest ironworking techniques arrived in India around 1500 BCE, initially concentrated in the north and gradually spreading southward. By the Gupta era, iron had become ubiquitous, playing a pivotal role in:

- Construction: From iconic monuments like the Iron Pillar of Delhi to intricate temple structures, iron provided a sturdy and versatile material for architects and builders. Archaeological evidence reveals the use of iron beams, nails, and clamps in Gupta-era constructions, showcasing their advanced metallurgical skills.

- Agriculture: Iron tools revolutionized farming practices. Studies suggest sturdier plows and implements increased agricultural productivity, contributing to the economic prosperity of the Gupta Empire. Archaeological finds of iron sickles, hoes, and axes further solidify this agricultural transformation.

- Military Might: The Gupta Empire wasn’t solely defined by peace and prosperity. To safeguard their vast territories, they established a formidable army equipped with iron weapons and armor. Studies suggest advancements in ironworking techniques led to the production of superior swords, spears, and helmets, contributing to the empire’s military prowess.

1000 CE: Iron Finds Its Way to Africa

Around 1000 CE, the transformative power of iron reached the diverse and vibrant continent of Africa. The Bantu peoples, renowned for their cultural dynamism, readily embraced ironworking technology. Studies suggest they adapted existing techniques to local resources, developing unique furnace designs and smelting processes. Archaeological evidence reveals a wide range of iron tools and weapons crafted by the Bantu, from hoes and axes for agriculture to spears and swords for defense and warfare. This independent adoption and adaptation of ironworking highlights the universality and transformative potential of this technology.

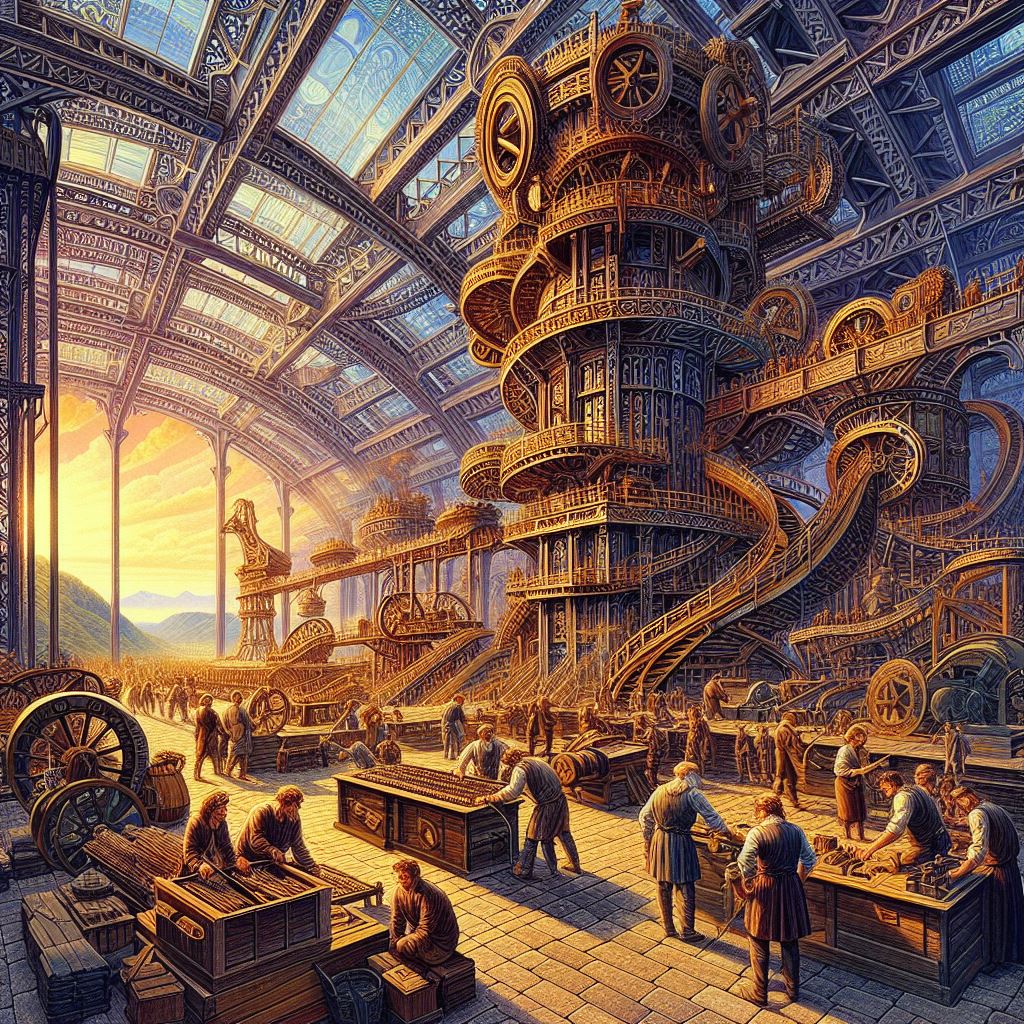

1700 CE: Iron’s Industrial Revolution in Europe

As the 18th century dawned, Europe stood at the precipice of a monumental shift – the Industrial Revolution. And at the heart of this revolution stood iron. Its uses transcended the traditional domains of tools and weapons, finding new applications in:

- Machinery: From the clattering looms of textile mills to the powerful engines driving steamboats and locomotives, iron became the essential material for building the machines that powered the Industrial Age. Studies suggest advancements in iron smelting and refining techniques, like the Bessemer process, drastically increased production and quality, enabling mass production and technological leaps.

- Construction: Iron bridges, towering factories, and expansive railway networks reshaped the landscape. Engineers harnessed the versatility and strength of iron to create structures that were previously unimaginable, transforming not only industries but also the built environment.

1900 CE: The Bessemer Process and the Steel Revolution

While the Bessemer process revolutionized steel production in the 19th century, its impact transcended mere mass production. It was a transformative leap, propelling humanity into a new era of engineering marvels and societal changes. Here’s a deeper dive:

- Before Bessemer: Prior to this innovation, steel was a luxury material, produced in limited quantities through laborious methods. This scarcity constrained its applications, impacting everything from construction to machinery.

- Bessemer’s Brilliance: In 1855, Henry Bessemer’s ingenuity unlocked steel’s full potential. His converter, using air blasts to remove impurities from molten iron, dramatically increased production and reduced costs.

- Steel’s Symphony: From towering skyscrapers like the Empire State Building to transcontinental railways and the iconic Eiffel Tower, steel became the backbone of modern infrastructure. Its strength, versatility, and durability redefined architecture, transportation, and countless other industries.

- Beyond Structures: The Bessemer revolution wasn’t just about physical landscapes. It transformed economies, creating new jobs and industries, and fueled rapid urbanization. The affordability and abundance of steel reshaped societies, influencing everything from cultural expressions to political landscapes.

21st century:

Iron’s story continues to unfold in the 21st century, not just in traditional applications but also in innovative frontiers:

- Green Technologies: Iron alloys play a crucial role in renewable energy technologies like wind turbines and solar panels. Research into new alloys with enhanced properties promises further advancements in this direction.

- Evolving Extraction: Advancements in ore extraction techniques, like bioleaching and hydrometallurgy, aim to reduce environmental impact and create more sustainable practices.

- Nanotechnology Revolution: The miniaturization trend extends to iron, with research into nanostructured iron alloys revealing promising applications in fields like biomedicine and electronics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, iron is one of the most important materials in human history, as it has been used for thousands of years to make weapons, tools, and other objects. The discovery of iron marked a significant shift in human technology and innovation and has played a vital role in the development of human civilizations. Iron technology continues to evolve and improve and its importance in human society shows no signs of diminishing.

Dive into more of my articles! Find my other blogs here: