Introduction: Solving the Longitude Problem

For centuries, navigating the open seas was a gamble. While sailors could track their latitude by measuring the sun’s angle above the horizon, determining longitude remained an unsolved puzzle. This challenge wasn’t just technical—it was a matter of survival. Entire fleets were lost, trade routes jeopardized, and naval dominance threatened, all because mariners could not reliably pinpoint their east–west position.

The breakthrough came with the timekeeper invention of the marine chronometer, a device that transformed global exploration. More than just a clock, it was a precision-engineered instrument that allowed sailors to calculate longitude with unprecedented accuracy. By carrying a reliable reference time at sea—something previously thought impossible—the chronometer turned ocean voyages from dangerous ventures into calculated journeys.

So, what is the chronometer? In simple terms, it is a highly accurate, portable timekeeping device designed to withstand the harsh conditions of long voyages. Its development marked a turning point in history, enabling safer exploration, global trade, and the expansion of empires. The marine chronometer wasn’t just a tool; it was the invention that unlocked the world’s oceans.

The Navigation Crisis Before the Chronometer

Before the invention of the marine chronometer, sailors were navigating half-blind. They could measure latitude by observing the altitude of the sun or Polaris (the North Star), but longitude was another matter entirely. Longitude required knowing the exact difference between local time at sea and the reference time at a fixed location (such as Greenwich). Without a reliable timekeeper, this calculation was impossible.

The consequences of this gap in the history of marine chronometer development were catastrophic:

- Shipwrecks – Vessels frequently struck reefs or ran aground because their estimated position was off by hundreds of miles.

- Lost cargo and fortunes – Merchant ships carried spices, textiles, and precious goods, and miscalculations often meant financial ruin.

- Naval disasters – Even powerful fleets weren’t immune. One of the most infamous tragedies, the 1707 Scilly naval disaster, claimed the lives of nearly 2,000 sailors when Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell’s fleet miscalculated its longitude and smashed into rocks.

Before chronometers, sailors relied on flawed methods:

- Dead reckoning – Estimating speed and direction over time, which compounded small errors into huge mistakes.

- Lunar distance method – Measuring the angle between the moon and stars to approximate time, but this was slow, required clear skies, and demanded advanced astronomical tables.

By the early 18th century, solving the longitude problem became a national obsession. In Britain, Parliament even passed the Longitude Act of 1714, offering a massive reward of up to £20,000 for anyone who could develop a practical solution. This crisis set the stage for innovators like John Harrison, whose marine chronometer would finally give sailors a dependable way to measure longitude and usher in a new era of safe global navigation.

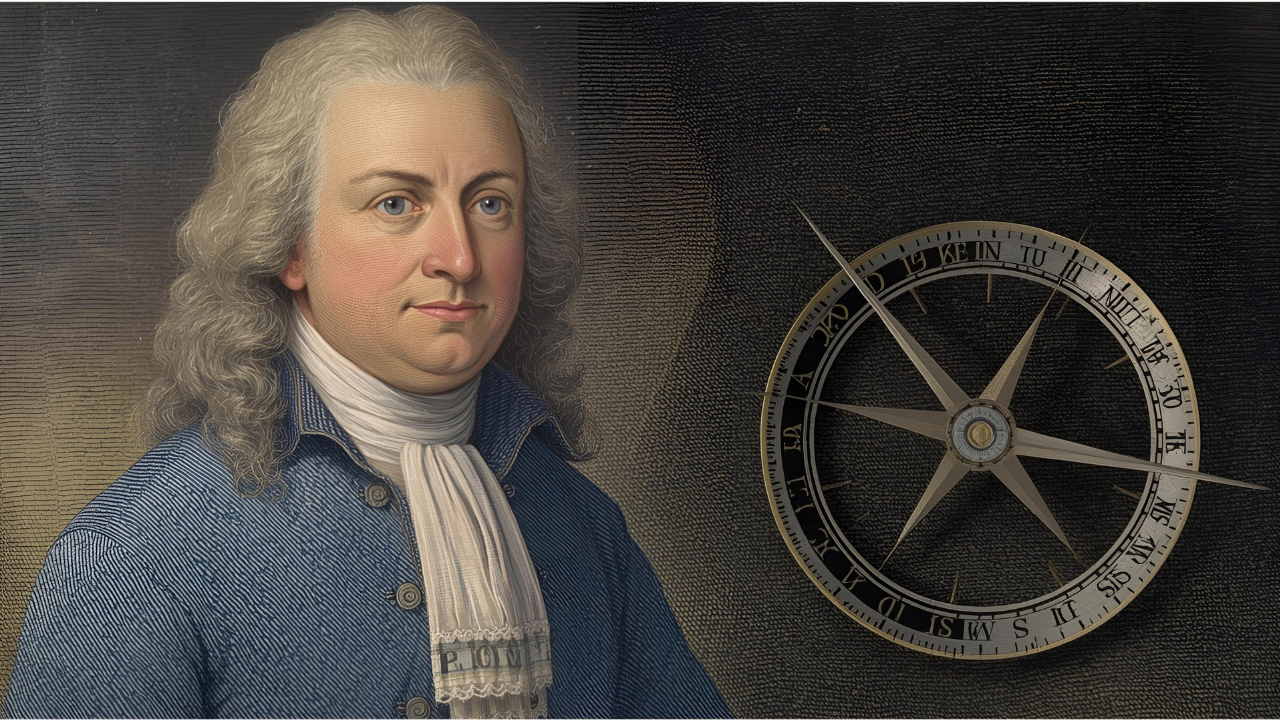

The Inventor – John Harrison’s Lifelong Mission

The marine chronometer inventor, John Harrison (1693–1776), was a self-taught English carpenter and clockmaker who dedicated his life to solving the greatest scientific challenge of his era: determining longitude at sea. Born in Yorkshire, Harrison showed an early fascination with mechanics and began building wooden clocks in his youth. His exceptional skill in precision craftsmanship quickly set him apart.

What drove Harrison was more than just ambition—it was an obsession with precision timekeeping. He believed that if a clock could keep accurate time aboard a ship, it would unlock the mystery of longitude. The problem? Clocks of the early 18th century were wildly unreliable at sea. Changes in temperature, humidity, and the constant rolling of ships caused pendulum clocks to lose or gain minutes daily—errors too large for safe navigation.

Harrison devoted decades to designing and refining a series of revolutionary timekeepers, from his early wooden longcase clocks to his groundbreaking portable chronometers (H1 through H5). His designs incorporated innovations like temperature-compensated balances, anti-friction devices, and ultra-precise gearing systems, making them resilient against the harshest conditions at sea.

But Harrison’s journey wasn’t smooth. The British government’s Board of Longitude, which oversaw the longitude prize, often doubted his approach. Astronomers favored celestial methods like the lunar distance technique, while many officials resisted the idea that a mechanical clock could ever remain reliable on long voyages. Despite this resistance, Harrison’s persistence eventually proved them wrong.

By the end of his life, the timekeeper invention of the marine chronometer secured his legacy as one of history’s most important inventors. Though recognition came slowly, John Harrison’s determination gave sailors the tool they had long needed to conquer the oceans.

The Longitude Act of 1714 and the Prize

The crisis of navigation had grown so severe by the early 18th century that it became a matter of national security. To safeguard its navy and commercial fleet, Britain passed the Longitude Act of 1714, establishing a prize of up to £20,000 (equivalent to millions today) for anyone who could provide a practical method of determining longitude at sea with accuracy.

The competition fueled a heated race between two camps:

- Astronomers, who supported the lunar distance method—measuring the moon’s position against the stars to calculate time. This approach was theoretically sound but required advanced tables, constant calculations, and clear skies, making it impractical for many voyages.

- Mechanics, led by John Harrison, who argued for a mechanical solution—a portable timekeeper that could retain reference time from Greenwich throughout a voyage.

The prize created enormous pressure and opportunity. Innovators across Europe experimented with astronomical tables, pendulum clocks, and mechanical devices, but most failed under the harsh realities of the sea. Harrison’s chronometers stood out because they worked reliably, even during long transatlantic voyages.

Although Harrison struggled for decades to receive the full reward—often facing skepticism and bureaucracy—his inventions eventually convinced the Board of Longitude. The chronometer’s success marked a turning point in the history of marine chronometer development, proving that precision mechanics could solve a problem that had stumped humanity for centuries.

The Longitude Act not only spurred the invention of the marine chronometer but also demonstrated how government-backed incentives could accelerate scientific and technological breakthroughs—a model still followed today.

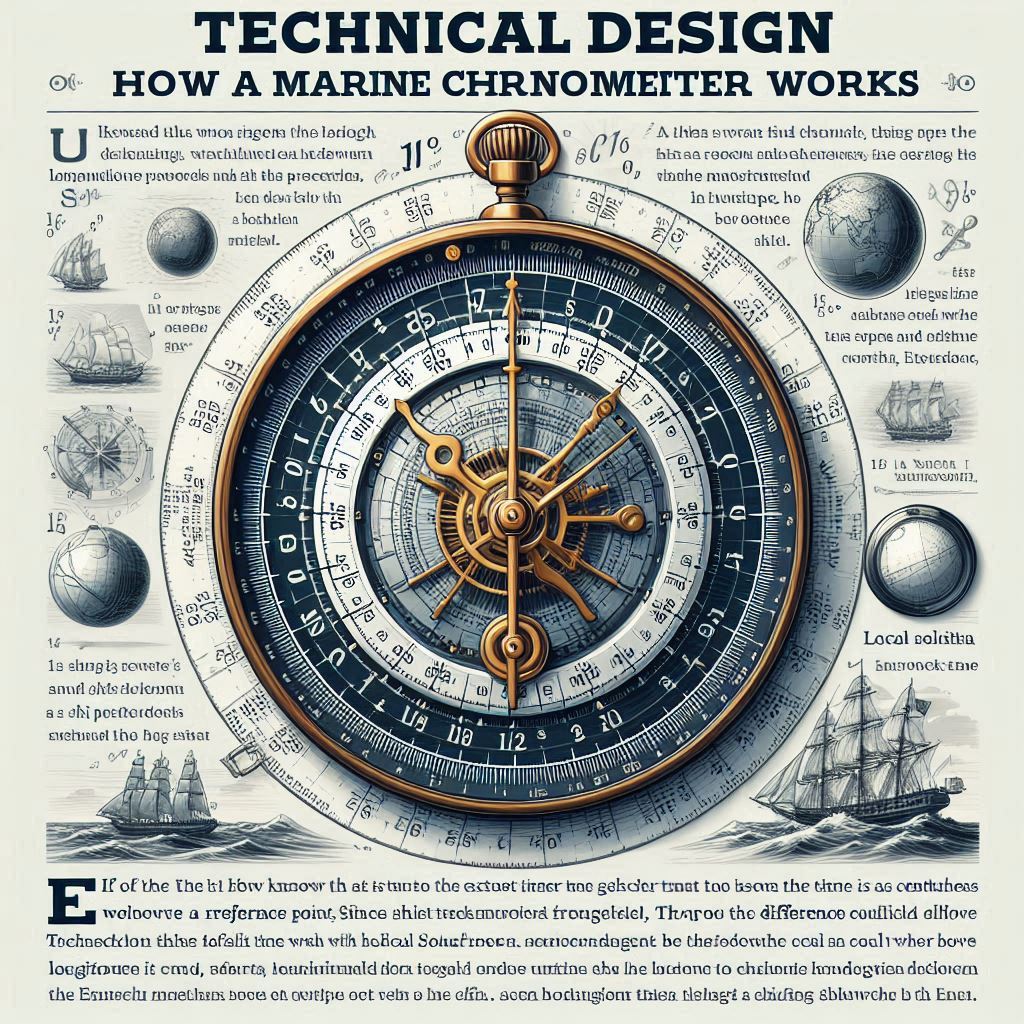

Technical Design – How a Marine Chronometer Works

To understand what is the chronometer, it’s important to see how it solved the centuries-old longitude problem. The principle is simple: if a sailor knows the exact time at a reference point (such as Greenwich, England) and compares it with local solar time determined at sea, the difference reveals longitude. Since the Earth rotates 15° per hour, even a one-minute error in timekeeping could throw a ship off course by 15 nautical miles. Precision was absolutely critical.

The genius of the timekeeper invention of marine chronometer lay in its mechanical innovations, designed to keep accurate time despite the rolling seas, shifting temperatures, and constant vibrations of a ship. Key features included:

- Balance spring and escapement – Replaced the pendulum, which was useless on a moving ship, with a resilient spring-driven balance wheel that oscillated steadily.

- Fusee and chain mechanism – Delivered consistent torque from the mainspring as it wound down, preventing time drift and ensuring accuracy throughout the voyage.

- Gimbal suspension – Mounted the chronometer in a set of rings, allowing it to remain level no matter how violently the ship pitched or rolled.

Other critical innovations were equally vital:

- Temperature compensation – Special bi-metallic strips adjusted for expansion and contraction of metal parts, preventing time variations caused by heat or cold.

- Shock resistance – Precision engineering reduced the impact of sudden jolts, a common hazard aboard wooden sailing vessels.

In short, the marine chronometer was more than a clock—it was a rugged, finely tuned scientific instrument. Its ability to maintain accurate time over long voyages made the timekeeper invention of marine chronometer one of history’s greatest breakthroughs in navigation.

The Breakthrough Models – H1 to H4

The path to a working chronometer wasn’t a single invention but a lifelong series of experiments by the marine chronometer inventor, John Harrison. Each model brought him closer to perfection:

- H1 (1735) – Harrison’s first marine timekeeper was massive, weighing 75 pounds, but it introduced crucial innovations like anti-friction wheels and a balance mechanism immune to a ship’s rocking. Tested at sea, it showed promise but was too large and complex for practical use.

- H2 (1741) – More compact than H1, with refinements in gearing and balance control. However, Harrison discovered design flaws that prevented consistent accuracy.

- H3 (1759) – Represented two decades of work. H3 introduced the bi-metallic strip for temperature compensation and a caged roller bearing system. Despite these advances, it still wasn’t precise enough for the Board of Longitude.

- H4 (1761) – The breakthrough. Unlike its predecessors, H4 resembled a large pocket watch, only 5 inches in diameter. It combined all of Harrison’s innovations into a portable, practical device. During its first sea trial to Jamaica, H4 lost only five seconds over 81 days at sea—an accuracy that stunned the scientific world.

The success of H4 finally convinced skeptics and cemented Harrison’s place in the history of marine chronometer. Though he struggled for years to gain full recognition and the prize money, his work proved beyond doubt that longitude could be solved mechanically.

The prototypes H1–H4 today stand as monuments to persistence and ingenuity, showing how the marine chronometer inventor turned a national crisis into one of the greatest triumphs of human innovation.

Impact on Navigation and Exploration

The timekeeper invention of marine chronometer completely changed the course of global navigation. Before its arrival, sailors relied on dead reckoning and lunar distance calculations, which were prone to major errors. With the chronometer, ships could finally measure longitude accurately by comparing local solar noon with the precise time at a reference location, usually Greenwich. This breakthrough meant voyages could be plotted with unprecedented safety and reliability.

For global trade, the chronometer was nothing short of revolutionary. Merchant vessels carrying valuable cargo could now travel across oceans with reduced risk of shipwreck or delay. The instrument also provided a strategic advantage: Britain’s naval supremacy during the 18th and 19th centuries owed much to the widespread adoption of chronometers, allowing fleets to coordinate movements and dominate sea routes.

Exploration benefited as well. Expeditions into the Pacific Ocean—from mapping distant archipelagos to charting unknown coastlines—relied on the chronometer for accuracy. Captain James Cook’s voyages, for instance, demonstrated its value in producing detailed and reliable maps. In short, this navigational instrument was the backbone of safer seafaring and global expansion.

Cultural and Scientific Significance

Beyond navigation, the marine chronometer became a cultural symbol of human ingenuity. It showed that persistence, engineering brilliance, and practical application could solve a problem that had baffled astronomers and scientists for centuries.

The chronometer also bridged disciplines. Its design was influenced by astronomy, since celestial movements inspired methods for calculating longitude. It advanced geography, by enabling precise map-making and exploration. And it pushed the boundaries of mechanical engineering, leading to innovations in temperature compensation, precision gears, and shock-resistant mechanisms.

The legacy of the chronometer extended into the future of timekeeping. It directly influenced the development of precision watches and scientific instruments, which became crucial not only for navigation but also for industries like railways, astronomy, and telecommunications.

Today, when people ask what is the chronometer, they are not just referring to a navigational device, but to an invention that reshaped both science and society. The history of marine chronometer reminds us that technological progress often begins with solving a practical human challenge—in this case, survival at sea.

Decline and Modern Legacy

By the 20th century, the marine chronometer faced powerful rivals in timekeeping. The rise of quartz watches, satellite-based GPS systems, and eventually atomic clocks made mechanical chronometers largely obsolete for practical navigation. Ships and navies no longer needed to rely on a box-bound mechanical device when electronic instruments could provide faster, cheaper, and more precise results.

However, the chronometer never truly disappeared. Today, it lives on as a collectible and luxury timepiece, admired for its craftsmanship and historical significance. Collectors and horology enthusiasts often seek rare examples of Harrison’s successors’ designs, many of which are auctioned online. For instance, searching for an eBay marine chronometer reveals dozens of antique models, some selling for thousands of dollars, reflecting the ongoing fascination with this pioneering navigational instrument.

The marine chronometer inventor, John Harrison, is now celebrated not just for solving the longitude problem but also for inspiring generations of watchmakers and engineers. His legacy lives on in both the history of science and the luxury watch market, where precision and beauty remain inseparable.

Conclusion – A Timekeeper That Changed the World

The timekeeper invention of marine chronometer stands as one of the greatest breakthroughs of the Industrial Age. More than a mechanical device, it was a solution to a life-or-death challenge that transformed navigation, enabled global trade, and fueled exploration. Without it, the expansion of empires, the exchange of goods, and the mapping of the world’s oceans would have been delayed by decades, if not centuries.

When people ask, what is the chronometer, the answer goes beyond gears, springs, and gimbals. It is the story of John Harrison’s relentless pursuit of precision, the triumph of engineering over uncertainty, and the invention that literally set the world in motion. Even though GPS and atomic clocks rule modern navigation, the chronometer remains a timeless symbol of human ingenuity and progress.

⛵ Interested in more fascinating inventions that shaped our world? Dive deeper into history with these articles: