Introduction: The Invention of Telegraph

In the annals of communication history, few inventions have had such a profound impact as the telegraph. Pioneered in the early 19th century, this ground-breaking technology transformed the way information was transmitted across long distances. In this blog, we will delve into the discovery of the telegraph, its timeline of evolution, and its enduring importance in shaping the world as we know it today.

As communication technologies weave an ever-expanding tapestry around us, it’s easy to forget the revolutionary threads that came before. The electric telegraph, born not in the digital age but in the early 19th century, stands as a testament to human ingenuity and its enduring impact on the course of history. This wasn’t just an invention; it was a gateway to a new era of long-distance communication, forever altering how information traveled and societies interacted.

While Samuel Morse often stands as the face of the telegraph, its journey is far richer than a single name. From the early whispers of static electricity explored by William Gilbert to the crucial connection between electricity and magnetism discovered by Hans Christian Oersted, the seeds of this technology were sown long before Morse began tinkering with his iconic code. This blog unveils the intricate story of the electric telegraph, delving into its conception, evolution, and enduring legacy. We’ll explore the key players, the technological advancements that paved the way, and the ripple effects that forever transformed the world.

Who Invented Telegraph:

The invention of telegraph by Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail, who, in the early 1830s, developed a system capable of transmitting messages using electrical signals. The breakthrough came with the invention of Morse code, a system of dots and dashes representing letters and numbers. In 1837, Morse and Vail successfully demonstrated their invention, forever changing the course of communication.

The Invention and History of Telegraph:

17th Century: Seeds of Discovery

While William Gilbert and Otto von Guericke made significant strides in understanding electricity, their work wasn’t an isolated endeavor. Lesser-known figures like Francis Hauksbee (1705) and Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan (1746) deserve recognition for their tireless exploration of static electricity. Hauksbee, through his experiments with evacuated tubes, discovered the phenomenon of “electrical glow,” paving the way for understanding electrical discharges. Mairan, on the other hand, investigated the electrostatic attraction and repulsion of charged objects, contributing valuable insights into the nature of electrical forces. These seemingly isolated experiments, conducted in the shadows of the giants, laid crucial groundwork for future advancements in electrical communication.

1753: Franklin’s Kite

Benjamin Franklin’s kite experiment in 1753 wasn’t just a daring stunt that captured the public imagination. His key contribution lay in proving the identity of lightning with electricity. This wasn’t merely a scientific curiosity; it was a fundamental shift in understanding that unlocked a new realm of possibilities. By demonstrating the electrical nature of lightning, Franklin opened the door to harnessing this powerful force for communication purposes. His experiment wasn’t the end, but a crucial stepping stone on the path towards electrical telegraphy.

1790s: Claude Chappe’s semaphore system

Claude Chappe’s semaphore system, with its innovative chain of towers and pivoting arms, wasn’t an isolated invention. While it garnered considerable attention in France, similar visual telegraphs emerged around the world, highlighting a shared human desire to overcome distance barriers.

Sweden (1794): Engineer Abraham Edelcrantz developed a semaphore system using movable boards on towers, demonstrating its effectiveness in conveying messages over long distances. Notably, his system preceded Chappe’s by four years, showcasing the parallel and independent pursuit of communication solutions.

Austria (1801): The Austrian semaphore system, designed by Ignaz Joseph Mitis, employed shutters instead of arms, achieving remarkable range and speed. Its implementation across the vast Austrian Empire further underscores the practical need and strategic value of rapid communication technologies.

These examples, along with Chappe’s system, reveal a global wave of innovation driven by the common challenge of conveying messages across vast distances. While each system had its unique features, they all shared the core principle of using visual signals to transmit information – a testament to the universality of human ingenuity.

Historical References:

- Abraham Edelcrantz: “Beskrifning öfver en ny Signal-Machin, at kunna gifva långväriga tecken” (1795)

- Ignaz Joseph Mitis: “Grundzüge der Zeichensprache zum Behufe der optischen Telegraphie” (1829)

- François Arago: “Historical Eloge of Abraham Edelcrantz” (1832)

- David Chandler: “Semaphore: The Language of Towers” (2008)

19th Century: The Rise of Electric Telegraphy:

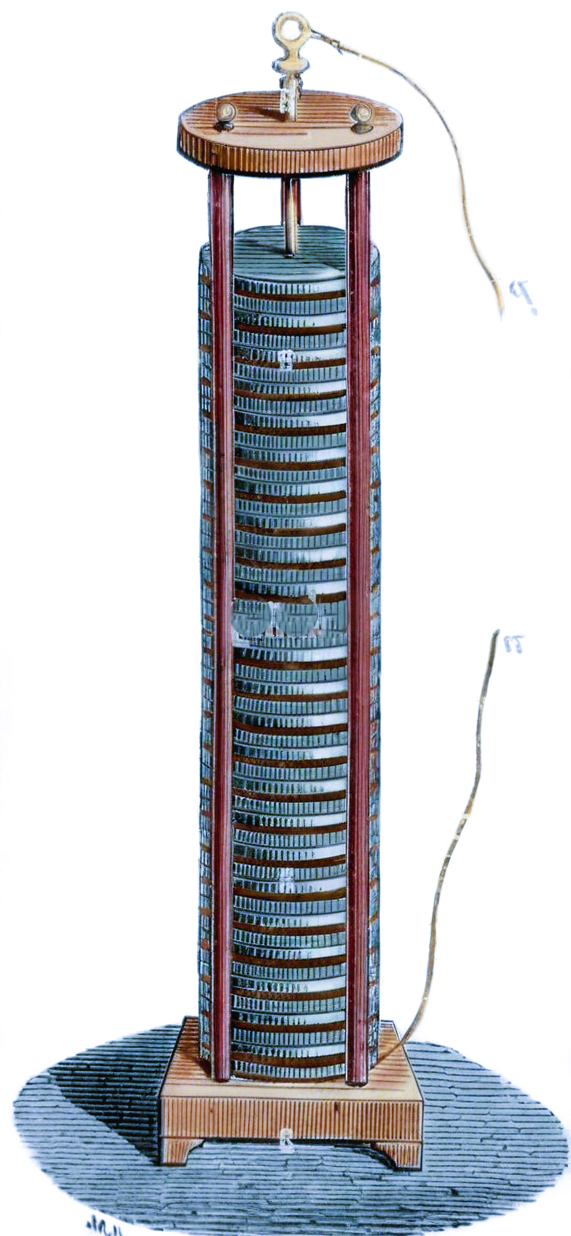

1800: Volta’s Pile

- “Not just an invention, but a revolution:” Alessandro Volta’s “voltaic pile” wasn’t merely a battery; it was a paradigm shift. Unlike earlier electrostatic generators, the pile provided a continuous and reliable source of current, essential for sustained electrical communication. This invention triggered a flurry of activity, with scientists like Johann Wilhelm Ritter using it to decompose water and Humphry Davy isolating new elements. Crucially, the pile became the heart of early telegraph prototypes, including those by Francesco Zambelli (1802) and Samuel Thomas von Sömmering (1809), setting the stage for future breakthroughs.

Historical References:

-

- Volta, Alessandro. “On the Electricity Excited by the Mere Contact of Conducting Substances of Different Kinds.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (1800).

- Knight, David M. “Volta and the Electric Battery.” The Chemical Educator (2004).

1820: Bridging Electricity and Magnetism:

- “More than a lab experiment:” Hans Christian Oersted’s 1820 discovery wasn’t just observing a compass needle deflecting near a current-carrying wire; it was a conceptual leap. He recognized the fundamental link between electricity and magnetism, envisioning the possibility of transmitting signals using this connection. This foresight became the guiding light for future inventors, inspiring figures like André-Marie Ampère to develop electromagnetism as a scientific discipline.

Historical References:

-

- Oersted, Hans Christian. “Experiments on the effect of a current of electricity on the needle of a compass.” Philosophical Magazine (1820).

- Peacock, Gary W. “Hans Christian Ørsted and the Discovery of Electromagnetism.” Journal of Chemical Education (1979).

1823: Sturgeon’s Electromagnet

- “A game-changer:” William Sturgeon’s electromagnet wasn’t simply a stronger magnet; it offered controllable magnetism generated by electricity. This was a missing piece in the telegraph puzzle. Earlier attempts relied on permanent magnets, limiting signal strength and distance. However, Sturgeon’s invention allowed for powerful, variable magnetic fields, paving the way for electromagnetic telegraphs like Joseph Henry’s (1831) and Samuel Morse’s successful system.

Historical References:

-

- Sturgeon, William. “Experiments on Electromagnetism.” Transactions of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce (1824).

- Moeller, R. Bruce. “Electromagnetism: A Brief History.” The Physics Teacher (1991).

Multiple Inventors and Early Systems:

1833:

1833 wasn’t just a year in history; it marked a pivotal moment in communication technology. While Carl Friedrich Gauss and Wilhelm Weber are rightly recognized as pioneers, their contribution deserves further analysis. They weren’t just renowned physicists; they were visionaries who dared to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. Their working telegraph prototype, though not commercially successful, represented a crucial proof of concept. It demonstrated the feasibility of using electromagnetism for long-distance communication, igniting the imaginations of future inventors and paving the way for the revolution to come.

Historical References:

- Wilhelm Eduard Weber | German physicist

1837:

The rivalry between Cooke & Wheatstone and Morse & Vail is certainly well-known, but your addition of Edward Davy paints a more nuanced picture. His 1836 telegraph patent submission highlights the competitive nature of innovation in the 19th century. This wasn’t a duel between two teams; it was a multifaceted race driven by ambition and the potential to revolutionize communication.

Deeper Than Single-Wire and Dot-Dash:

While Morse & Vail’s single-wire system and dot-and-dash code were undoubtedly key innovations, their contribution extended beyond technological advancements. Recognizing the crucial partnership between Morse and Vail is essential. Morse, with his political connections and fundraising skills, secured financial backing and public attention. Vail, on the other hand, was the technical mastermind, tirelessly improving the telegraph’s design and functionality. Their complementary skills and close collaboration were critical to their success.

References:

Morse Rises to Prominence:

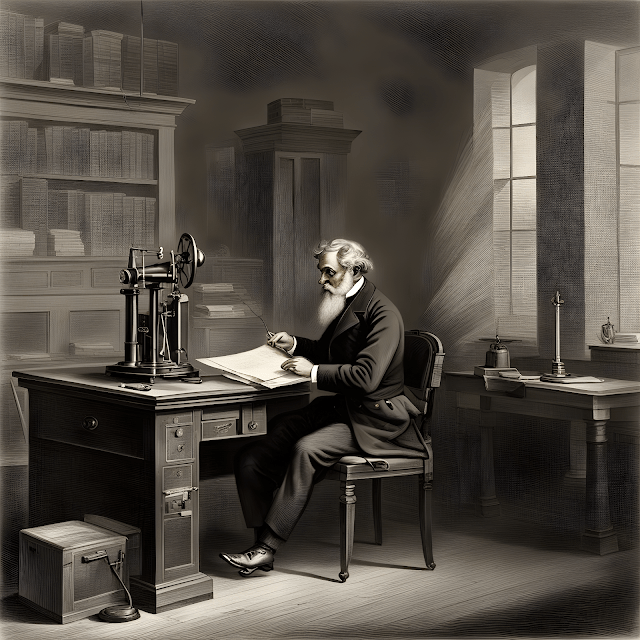

1844: Samuel Morse-“What hath God wrought?”

The iconic message “What hath God wrought?” sent by Samuel Morse in 1844 resonated far beyond the initial awe. It wasn’t merely a successful test; it was a powerful demonstration of the telegraph’s potential to revolutionize communication. This public spectacle captured the imagination of the masses, newspapers hailed it as a “miracle,” and investors saw the boundless possibilities for business and government. This moment proved pivotal in securing funding for further development, propelling the telegraph from a laboratory curiosity to a viable technology poised to transform the world.

Historical References:

- “The Electro-Magnetic Telegraph” by Alfred Vail (1845): A firsthand account of the development and demonstration of the telegraph, including the iconic message.

- “The American Telegraphic Journal and Electrical Review” (1867): An early periodical chronicling the advancements and impacts of the telegraph.

- “Inventing the Telegraph” by David Bodanis (2002): A comprehensive narrative exploring the inventors, challenges, and societal impact of the telegraph.

1845:

While the inauguration of the Washington-Baltimore telegraph line in 1845 marked a historical first, its significance went far beyond mere novelty. This crucial link demonstrated the telegraph’s practicality in real-world communication. News stories traveled in minutes, stock prices fluctuated instantaneously, and government messages reached officials with unprecedented speed. This success story fueled public confidence and investment, paving the way for the widespread adoption of the technology across the nation and beyond.

Historical References:

- “The History of the United States Telegraph” by James D. Reid (1879): A detailed look at the development and expansion of the American telegraph system.

- “The Atlantic Monthly” (October 1845): An early article detailing the operations of the Washington-Baltimore line and its impact on society.

- “The Telegraph and the Railroads” by Robert C. Allen (1994): Explores the intertwined history of the telegraph and the development of modern transportation networks.

1851:

Cyrus Field’s proposal for a transatlantic telegraph cable in 1851, though initially unsuccessful, wasn’t merely an ambitious goal; it was a visionary act that sparked a technological odyssey. The immense technical and logistical challenges were daunting, and the first two attempts ended in failure. Yet, Field’s audacity and unwavering belief in the project’s potential kept him going. In 1866, after years of persistence and technological advancements, the dream finally became reality. This monumental achievement not only revolutionized transatlantic communication but also symbolized the power of visionary thinking in overcoming seemingly insurmountable hurdles.

Historical References:

- “The Great Atlantic Telegraph: A History of the Project” by James D. Bulloch (1858): A detailed account of the first transatlantic cable project, including its challenges and setbacks.

- “Cyrus W. Field and the Atlantic Cable” by James D. Reid (1896): A biography of Field, highlighting his vision, perseverance, and impact on communication technology.

- “The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Making of the Modern World” by Tom Standage (2014): Provides a broader context for the transatlantic cable project and its historical significance.

Expansion and Innovation:

1861: Western Union – From Mergers to Monopoly

While Western Union’s dominance is well-known, the story behind its rise holds fascinating complexities. It wasn’t just a single company; it was the result of a series of strategic mergers orchestrated by Hiram Sibley. In 1855, Sibley, a lawyer and businessman, saw the immense potential of the telegraph industry and began acquiring smaller telegraph companies. By 1861, he had merged six major concerns into the Western Union Telegraph Company, creating a near-monopoly that controlled over 90% of telegraph lines in the US.

This wasn’t just an economic feat; it had significant social and political implications. Western Union’s control over communication infrastructure allowed them to influence news dissemination, stock markets, and even government decisions. The company faced accusations of using its power unfairly, highlighting the complex relationship between monopolies and technological innovation.

Historical References:

- “The Coming of the Corporation: A History of American Business and Public Policy” by Alfred D. Chandler Jr.

- “The Western Union Telegraph Company: A History” by Robert Luther Thompson

- “The Great Atlantic Conspiracy: The Supporters and Enemies of the Transatlantic Cable, 1856-1866” by James Mackay

1866: The Transatlantic Cable

The transatlantic cable, successfully laid in 1866, was more than just an engineering marvel. It was a cultural and political milestone, instantly connecting Europe and America. This previously unimaginable feat revolutionized communication, impacting news, business, and diplomacy.

News: Transatlantic communication became nearly instantaneous, allowing newspapers to publish timely reports from abroad and shaping global public opinion.

Business: Trade and financial transactions could be conducted much faster, leading to increased efficiency and interconnectedness.

Diplomacy: Communication between governments became more immediate, influencing international relations and crisis management.

However, the story wasn’t without its challenges. The cable faced technical difficulties, repair expeditions were costly, and message transmission remained expensive for ordinary citizens. Despite these obstacles, the transatlantic cable symbolized a new era of global connectivity and laid the foundation for future communication technologies.

Historical References:

- “The Atlantic Cable” by Charles Bright

- “The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century” by Tom Standage

- “God’s Continent: America’s Nineteenth-Century Religious Crisis and the Rise of Modernity” by Matthew Bowman

1872: Alexander Graham Bell

While Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone initially seemed like a novelty, it was a paradigm shift in communication. Unlike the telegraph, which required knowledge of Morse code and specialized equipment, the telephone offered immediacy, ease of use, and real-time voice communication. This made it accessible to a wider audience, gradually challenging the telegraph’s dominance.

Social Impact: The telephone revolutionized personal communication, fostering closer connections across physical distances. It also transformed businesses, allowing for direct conversations and negotiations, leading to increased efficiency and new opportunities.

Cultural Impact: The telephone became a symbol of modernity and progress, influencing popular culture and literature. It also raised privacy concerns and ethical questions about eavesdropping and monitoring conversations.

Technical Advancements: Bell’s invention sparked further innovations, paving the way for switchboards, long-distance calls, and ultimately, the modern telephone network.

Historical References:

- “The Telephone: The First Hundred Years” by John Brooks

- “Alexander Graham Bell: The Inventor Who Changed the World” by Katherine Halliwell

- “The Victorian Telephone: The Making and Unmaking of a Communication System” by Janet Abbate

Later Developments and Legacy:

1890s-1920s: Changing Landscape

The telegraph’s decline in the late 19th and early 20th centuries wasn’t solely a matter of technology outpacing it. It was a symphony of societal shifts and technological advancements:

- The Rise of the Voice: The invention of the telephone in 1876 offered instantaneous, two-way communication, a stark contrast to the telegraph’s delayed, one-way messages. This immediacy resonated with businesses and individuals, gradually shifting communication preferences.

- The Power of Radio: Guglielmo Marconi’s wireless telegraph (1896) offered unprecedented mobility and reach, sending messages across oceans without cables. This flexibility, coupled with the rise of public radio broadcasting, further eroded the telegraph’s dominance.

- Faster & Cheaper: Teletypes, introduced in the early 20th century, provided faster transmission speeds and lower costs compared to traditional telegraphs. However, they couldn’t compete with the growing affordability and convenience of telephones.

Historical References:

- Tom Standage, “The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s Communications Revolution”

- Jeffrey Kiebuzinski, “The Telephone and American Life, 1876-1920”

Mid-20th Century:

While eclipsed by newer technologies, the telegraph didn’t vanish. Its reliability and long-distance capabilities proved valuable in specific contexts:

- Military Communication: The telegraph remained a crucial tool for secure, long-range communication during World War I and II. Its ability to transmit coded messages without being easily intercepted made it invaluable for military operations.

- Emergency Situations: The telegraph’s resistance to interference and its ability to operate in harsh conditions made it a reliable lifeline in emergencies like floods, earthquakes, and other disasters.

- Remote Areas: In geographically isolated regions with limited infrastructure, the telegraph continued to be a vital link to the outside world, facilitating communication and coordination.

Historical References:

- David Kahn, “The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing”

- Gerard J. DeGroot, “The Atlantic Cable: The Submarine Telegraph and Quaker Commercial Diplomacy”

Present Day:

The telegraph may not be the communication king anymore, but it hasn’t faded entirely. Niche applications continue to utilize its unique strengths:

- Underwater Communication: In environments where radio waves cannot penetrate, such as deep oceans, underwater cables powered by telegraph technology still transmit vital data and messages.

- Military Applications: Some militaries still maintain secure telegraph networks for specific communication needs, valuing their resilience and resistance to interception.

- Historical Preservation: Enthusiasts and historical societies preserve and operate antique telegraph equipment, showcasing its technological heritage and providing educational experiences.

Historical References:

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), “Undersea Cable Program”

- National Museum of American History, “The Morse Telegraph”

The telegraph’s story reminds us that technology isn’t always a linear progression towards faster and flashier solutions. Sometimes, older technologies retain value due to their unique characteristics or suitability for specific contexts. By understanding the historical and social factors that shaped its development and decline, we gain a richer appreciation for the telegraph’s enduring legacy, even in a world dominated by instant communication.

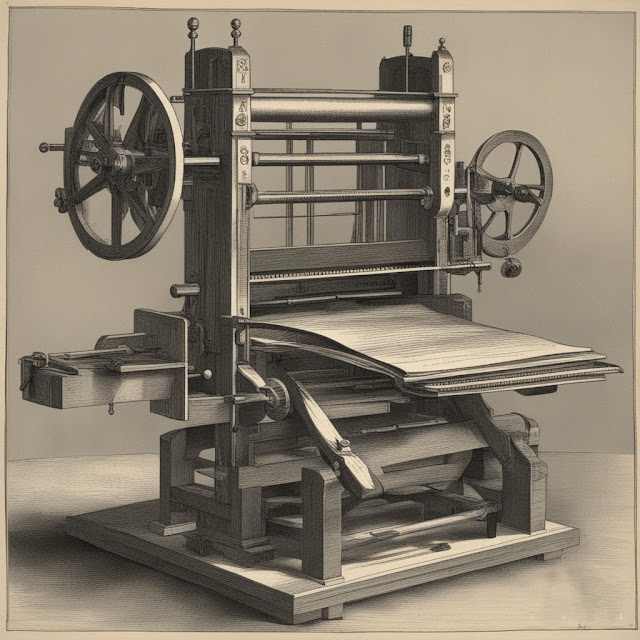

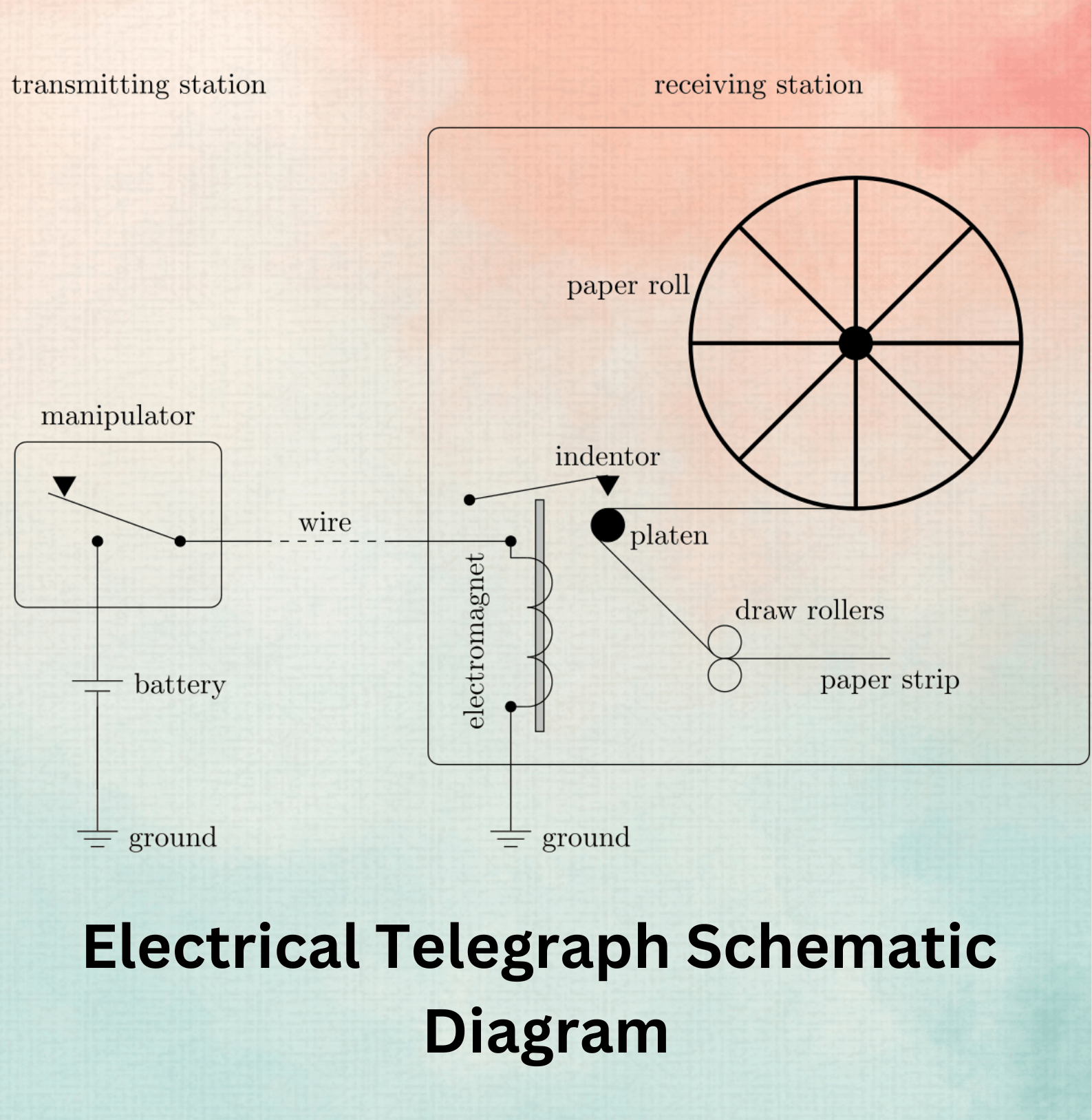

How Telegraph works

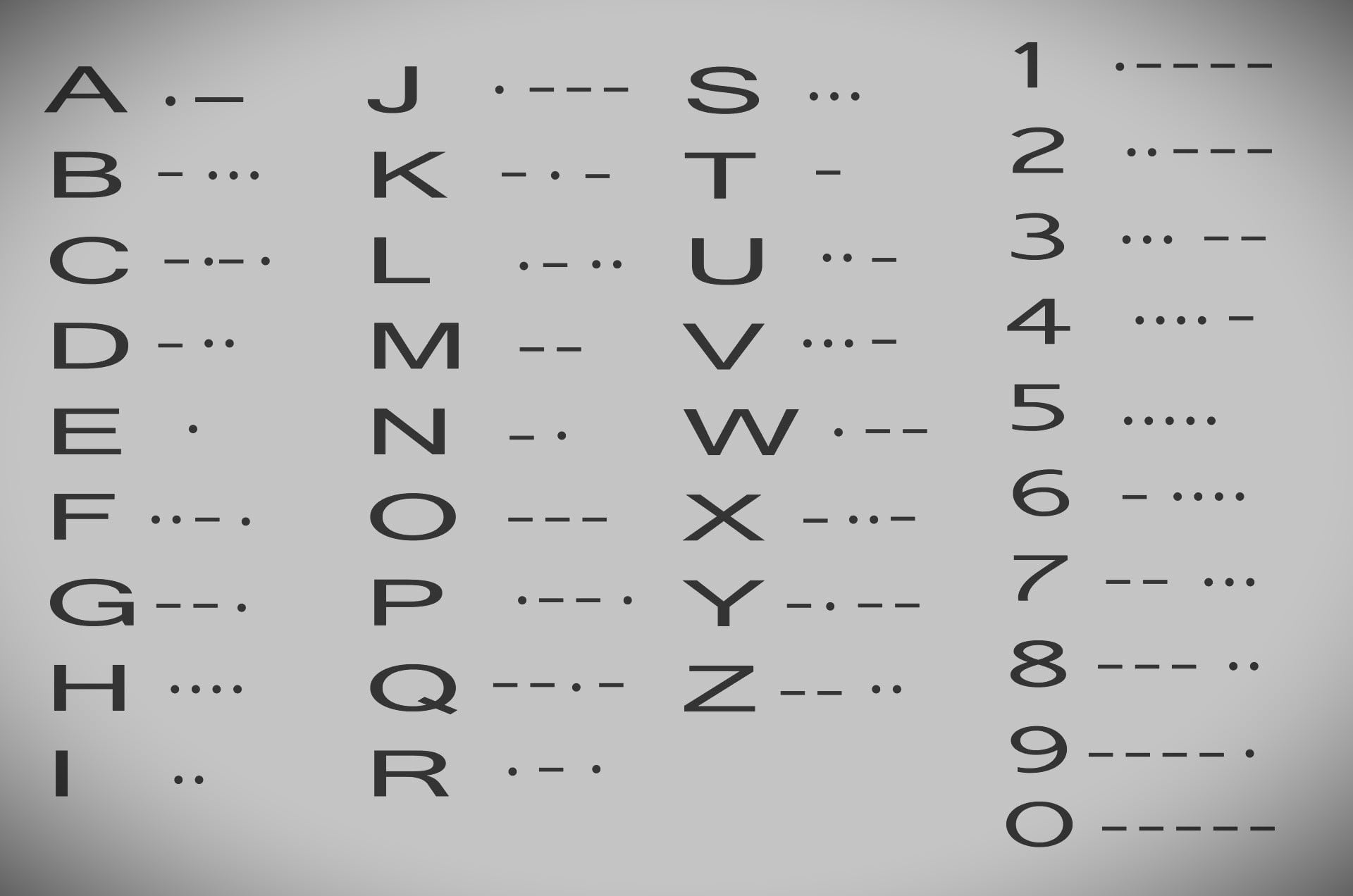

While Morse code may appear simple, it was a masterfully crafted language optimized for the limitations of early electrical signaling. Each letter, number, and punctuation mark received a unique combination of dots and dashes, allowing efficient transmission and unambiguous interpretation. Just like musical notes on a staff, these dots and dashes represented varying durations of electrical current, carrying the essence of the message across wires.

Telegraph Lines: The Information Highways of the 19th Century:

Imagine a network of copper veins crisscrossing continents, carrying the lifeblood of information. These were the telegraph lines, often strung on towering poles or buried underground. They facilitated the flow of electrical signals, bridging vast distances and shrinking the world for countless individuals.

Electric Current: The Invisible Messenger:

The invisible hero of the telegraph saga is the electric current. By pressing the telegraph key, the sender initiated a surge of electricity through the lines, transforming information into an electrical pulse. This pulse, carrying the encoded message, raced across the wires, defying geographical barriers and connecting minds separated by miles.

Electromagnets: The Heartbeat of Reception:

At the receiving station, waiting patiently, resided the electromagnet. This ingenious device transformed the incoming electrical signal back into a physical manifestation. As the current pulsed through the wires, it induced a corresponding magnetic field in the electromagnet, acting like a sensitive translator.

Encoding and Decoding: The Art of Translation:

The pulsing magnetic field of the electromagnet provided the crucial link between electricity and human comprehension. Depending on the duration of the current (dot or dash), the electromagnet would click or vibrate, creating a distinct, audible sound. Skilled operators, trained in the language of Morse code, could effortlessly interpret these clicks, converting them back into letters and words.

Sound or Markings: Capturing the Message:

For added reliability, some receivers employed paper tape recorders. As the electromagnet moved, it would mark the tape, creating a permanent record of the received message. Imagine the thrill of seeing these “printed” messages emerge, tangible proof of communication across vast distances.

Interpretation: From Clicks to Clarity:

The final act in this communication ballet involved the human element. The experienced operator, armed with their knowledge of Morse code, listened intently to the clicking sounds or deciphered the markings on the paper tape. With remarkable skill and speed, they translated these electrical echoes back into understandable language, bridging the gap between sender and receiver.

Response: A Two-Way Symphony:

The beauty of the telegraph lay not just in sending, but also in its ability to facilitate two-way communication. Just like the sender, the receiver could utilize the same system to send a response, creating a true dialogue across the wires. This back-and-forth exchange of information revolutionized communication, fostering collaboration, trade, and understanding on a global scale.

How Telegraph works- check out the video

The Basics of Morse Code:

- Morse code uses a simple but powerful concept: each letter, number, and symbol is represented by a unique combination of dots and dashes, also known as “dits” and “dahs.”

- The code is designed for transmission using sound, light, or other methods that can convey short and long signals effectively. It’s notable for its adaptability across different communication mediums.

- To distinguish individual characters and separate words, Morse code employs varying lengths of pauses or spaces.

Representing the Morse code Alphabet:

Let’s start with the representation of the English alphabet in Morse code. Here are some examples:

A (. -): The letter ‘A’ is represented by a single dot followed by a dash.

B (- . . .): ‘B’ consists of a dash followed by three dots.

C (- . – .): ‘C’ is depicted by a dash, a dot, a dash, and another dot.

D (- . .): ‘D’ is simply a dash followed by two dots.

E (.): The letter ‘E’ is represented by a single dot, making it the shortest Morse code character.

F (. . – .): ‘F’ combines two dots, a dash, and another dot.

G (- – .): ‘G’ is conveyed with two dashes and a single dot.

H (. . . .): ‘H’ is represented by four consecutive dots.

I (. .): ‘I’ consists of two dots.

J (. – – -): ‘J’ is formed by a dot followed by three

dashes.

Numbers and Punctuation:

Morse code goes beyond the alphabet; it also represents numbers and various punctuation marks. Here are a few examples:

1 (. – – – -): The number ‘1’ is indicated by a dot followed by four dashes.

2 (. . – – -): ‘2’ uses two dots and three dashes.

3 (. . . – -): ‘3’ combines three dots with two dashes.

4 (. . . . -): ‘4’ is formed by four dots and a dash.

5 (. . . . .): ‘5’ consists of five consecutive dots.

Period (.): The dot in Morse code represents a period or

full stop.

Comma (- – . . – -): The comma is depicted by two dashes, two

Importance and Legacy of the Telegraph:

The telegraph’s impact on society cannot be overstated. It revolutionized business, allowing companies to transmit orders, market data, and financial information across vast distances with unprecedented speed. It transformed journalism, enabling news agencies to relay breaking news across continents almost instantaneously.

Moreover, the telegraph fostered a sense of interconnectedness, shrinking the world and bridging the gaps between distant regions. It laid the foundation for global communication networks and paved the way for subsequent advancements, such as the telephone, radio, and the internet.

While the telegraph is now considered obsolete, its influence remains palpable. It serves as a testament to human ingenuity, marking a turning point in our ability to communicate across time and space. The telegraph’s enduring legacy reminds us of the remarkable progress we have made in the realm of communication technology.

Conclusion:

The telegraph was invented by the collaboration of Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail, and revolutionized communication in the 19th century. From its humble beginnings to the establishment of transatlantic connections, the telegraph network rapidly expanded, transforming various aspects of society. Its importance cannot be overstated, as it laid the foundation for modern global communication systems. Although the telegraph has been surpassed by more advanced technologies, its legacy endures as a testament to human innovation.

Also check out our other interesting blogs: