Introduction- The History of Mechanical Reaper

In the realm of agriculture, a reaper refers to a farm machine specifically designed to cut and gather cereal crops like wheat, barley, and rye. Imagine a streamlined chariot pulled by horses or tractors, equipped with a blade or series of blades that efficiently slice through stalks, marking a significant evolution from the time-consuming and laborious task of manual harvesting.

Early reapers, dating back to the 18th century, were relatively simple machines that primarily focused on cutting the crops, leaving the gathered stalks on the ground for manual bundling later. These initial models, while groundbreaking in their time, still required significant manual labor for the complete harvesting process.

As technology advanced, reapers became more sophisticated, incorporating mechanisms for binding the sheaves of cut stalks directly. This innovation, implemented in the late 19th century, further streamlined the harvesting process, reducing the need for additional manpower and significantly increasing overall efficiency.

The invention of the Mechanical reaper revolutionized the farming industry, allowing farmers to harvest crops more efficiently and on a larger scale. In this blog, we’ll take a closer look at the mechanical reaper story, its history, and its impact on agriculture.

Before Reaper-

Before the invention of the reaper, farming practices were much more labor-intensive and time-consuming. The reaper, a machine used for harvesting grain crops, revolutionized the agricultural industry by automating the harvesting process.

Prior to the reaper, farmers relied on manual methods to harvest crops. They typically used handheld tools such as sickles or scythes to cut the crops by hand. This process required a significant amount of physical labor, as farmers had to bend down and swing the tool repeatedly to cut the crops close to the ground. It was a slow and arduous task, especially when dealing with large fields.

The invention of the reaper machine, attributed to Cyrus McCormick in the early 19th century, brought about a significant change in farming efficiency. The reaper was a horse-drawn machine equipped with a cutting mechanism that could harvest crops more quickly and efficiently. It featured a series of reciprocating knives that would cut the crops as the machine moved forward. The harvested grain would then be collected and tied into bundles by the machine.

Before the invention of reaper, farmers required large quantities of labor for harvesting big farms. It was a time-consuming, labor-intensive and costly process. But with the introduction of the reaper productivity of farmers has improved now farmers can easily harvest large quantities of crops in shorter periods. It makes the invention of the Reaper is one of the important discoveries in the agriculture sector which made possible the increased food production and reduced labor requirements.

What is a Reaper?

A reaper is a simple farming tool that is used to harvest crops like wheat, rice, oats, and barley when they ripe. It is used for cutting the grain stalks and also separating the grains from its straw. Hand reaping it is done by various methods like plucking ears of grain directly by hand or cutting grain stalks with a sickle but after the discovery of reaper, this process is much easier, more economical faster and more efficient compared to traditional manual harvesting.

History of the Mechanical Reaper Machine

The first Mechanical reaper machine was invented by American inventor Cyrus McCormick in 1831. McCormick was the eldest son of Robert McCormick who was a farmer, blacksmith and inventor. McCormik’s education was limited which he completed from the local school, he was determined, serious-minded and spent most of his time in his father’s workshop. After watching his father struggle to harvest crops manually, he decided to create the machine. He began developing the reaper while still in his teens, work several years without success and by 1831, he had built a working prototype. Later in 1837, he set up a factory in Chicago which eventually became one of the greatest industrial establishments in the United States.

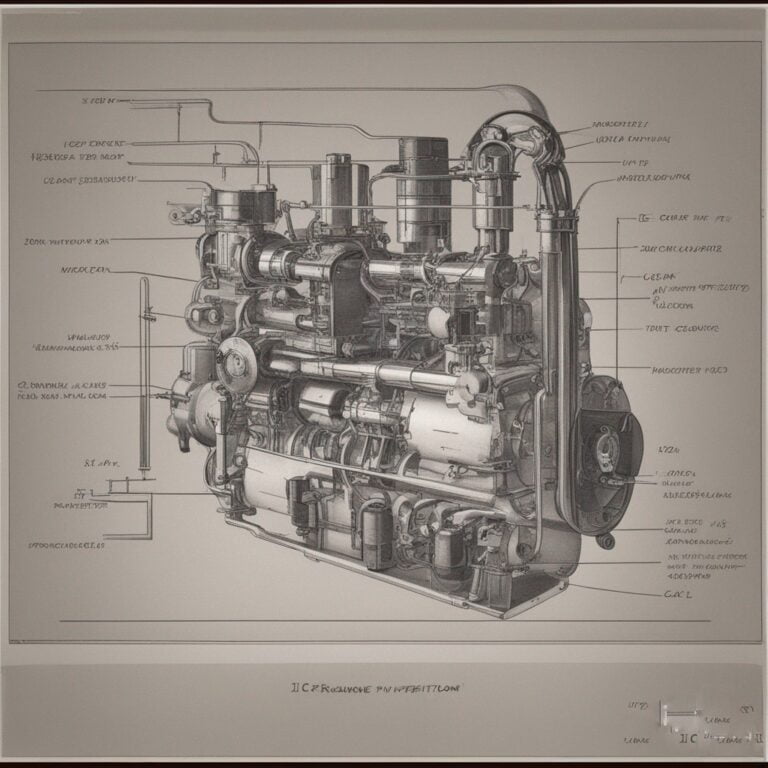

The original reaper is a horse-driven machine with a series of sharp blades that cut the grain stalks. The grain was then separated from the straw using a series of rakes and other mechanisms. McCormick kept improving the design of the reaper over the next several years, adding features like a canvas conveyor belt to transport the grain and a platform for the operator to stand on.

Timeline-

The history of agricultural machinery took a significant turn in the early 19th century when American inventor Cyrus McCormick introduced the first mechanical reaper. This invention would forever transform the way crops were harvested, making it more efficient and less labor-intensive.

Pre-1800: Seeds of Mechanization in a Field of Labor

While sickles and scythes had served farmers for millennia, harvesting remained a backbreaking, time-consuming affair. Imagine the countless hours spent bent over, hand-cutting grain under the scorching sun. This arduous reality sparked the seeds of mechanization in the minds of several inventors.

1784: Across the Atlantic, in Europe, Joseph Boyce patented the first recorded reaper design. However, its complexity and limited practicality prevented widespread adoption.

1798: The American spirit of innovation also took root in the fertile plains. Richard French crafted a reaper prototype utilizing a horse-drawn mechanism, but it lacked efficiency and reliability.

These early attempts, while unsuccessful in their own right, laid the groundwork for future advancements. They highlighted the potential of mechanization to alleviate the burden on farmers and revolutionize agricultural practices.

Historical References:

- “Scythes and Sickles: The History of Reaping Tools” by Peter Smith explores the evolution of hand-harvesting tools and their limitations.

- “The Mechanization of Agriculture in the 18th Century” by Rosalind Mitchison explores the broader context of agricultural innovation in Europe during this period.

1800-1833: From Prototype to Patent Battles:

Obed Hussey, a farmer from Maine, witnessed firsthand the challenges of manual harvesting. In 1826, he unveiled his groundbreaking prototype. Unlike previous attempts, Hussey’s reaper utilized a revolving reel to gather grain and a reciprocating blade to cut it, offering a glimpse of practical efficiency.

However, Hussey’s invention wasn’t the only contender in the race for mechanized reaping. William Manning and J.T. Bell also filed patents for reaper designs, igniting a fierce legal battle over claims of prior invention and infringement. This period of patent disputes, while hindering progress momentarily, also underscored the immense interest and potential surrounding the reaper technology.

Historical References:

- “The Reaper Case: Cyrus McCormick and the Patent Wars” by Willard H. Dowd delves into the legal complexities surrounding the invention of the reaper.

- “Obed Hussey: The Forgotten Inventor of the Reaper” by Robert G. Athearn sheds light on Hussey’s contributions and his place in the reaper story.

1834: Cyrus McCormick Patents the Reaper and Its Impact Begins

In 1834, Cyrus McCormick patented his groundbreaking invention, the reaper. This reaper by Cyrus McCormick was designed to cut and gather ripe grain quickly and efficiently, marking the dawn of a new era in agriculture. McCormick saw the potential to revolutionize farming by automating the laborious process of cutting and bundling crops, particularly wheat.

Cyrus McCormick’s reaper wasn’t just a patented invention; it was a catalyst for change. His vision to automate the arduous process of grain harvesting addressed a major bottleneck in agriculture. Imagine vast fields, teeming with ripe grain, and the backbreaking labor required to scythe and bundle them by hand. McCormick’s reaper, with its horse-drawn design, vibrating blade, and gathering platform, promised efficiency and speed. This wasn’t just an invention; it was a seed sown for a new era in agricultural productivity.

Historical References:

- James C. Davis, “The American Farmer in the Industrial Age” explores the impact of technological advancements like McCormick’s reaper on American agriculture.

- R. Douglas Hurt, “American Agriculture in the Nineteenth Century: Key Documents” provides primary sources showcasing the changing landscape of farming practices.

1851: International Acclaim at the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London wasn’t just a showcase of inventions; it was a global platform. McCormick’s reaper, amidst stiff competition, won the prestigious gold medal. This recognition wasn’t just a personal victory; it validated the potential of his invention on a global stage. The reaper’s efficiency and labor-saving capabilities resonated with farmers worldwide, paving the way for its adoption and adaptation across different agricultural landscapes.

Studies and Impact:

- Erik Foner, “Give Me Liberty! An American History” explores the wider economic and social impact of the reaper, including its contribution to increased agricultural production and westward expansion.

- Peter Temin, “A History of Technology” analyzes the long-term economic consequences of the reaper, highlighting its role in productivity gains and labor displacement.

1873: Formation of the International Harvester Company

In 1873, the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company merged with several other agricultural machinery manufacturers, including Deering Harvester Company and Plano Manufacturing Company, to form the International Harvester Company. This merger solidified the company’s position as a leading producer of agricultural equipment and machinery.

The formation of the International Harvester Company wasn’t just a merger; it was a strategic consolidation. Recognizing the growing market for agricultural machinery, McCormick joined forces with competitors like Deering and Plano. This created a dominant force in the industry, streamlining production, distribution, and marketing. It also signaled the increasing demand for mechanized farming solutions, driven by factors like population growth and urbanization.

Studies:

- University of Chicago Press, “Agricultural History” publishes research exploring the economic and social impact of agricultural machinery, including the reaper.

- National Bureau of Economic Research, “The Impact of Technological Change on Agriculture” analyzes the long-term effects of mechanization on agricultural productivity and labor patterns.

1880s-1890s: Continuous Innovation and Improvement

This period wasn’t just about “continuous improvement”; it was a vibrant tapestry of competing ideas and innovations. John Appleby introduced the automatic binder in 1881, revolutionizing the backbreaking task of tying bundles. Meanwhile, Cyrus McCormick Jr. focused on self-propulsion, culminating in the steam-powered reaper in the 1890s. These advancements weren’t just technical; they reflected a growing understanding of efficiency, ergonomics, and agricultural needs.

Historical References:

- “Reaping the Benefits: The Cyrus McCormick Reaper and the Rise of American Agriculture” by R. Douglas Hurt delves into the social and economic impact of McCormick’s reaper.

- “Harvesting the Land: A History of American Agriculture” by Paul Wallace Gates provides a broader context for the evolution of agricultural machinery.

Short Story of Inventors:

Imagine John Appleby, a farmer himself, witnessing the drudgery of hand-tying bundles. Fueled by empathy and a practical mind, he dedicates years to crafting the automatic binder, a testament to the ingenuity often found amongst those closest to the problem.

1902: The Birth of the Combined Harvester

Hiram Moore’s combined harvester wasn’t just a machine; it was a paradigm shift. It eliminated the need for separate reaping and threshing, reducing labor costs and increasing harvesting speed. This “one-stop shop” approach revolutionized the industry, paving the way for further advancements.

Historical Reference:

- “The Combined Harvester: A History of the Forerunner of Modern Farm Machinery” by Robert C. Williams offers a detailed analysis of the combined harvester’s development and impact.

1930s: Global Adoption of the Reaper

The reaper’s journey wasn’t limited to the American Midwest. As European and Asian economies modernized, they embraced the labor-saving potential of the reaper. This global adoption showcased the technology’s versatility and its ability to transform agricultural practices across continents.

Short Story:

Imagine a Japanese farmer, initially skeptical of the “Western machine,” witnessing the reaper’s efficiency in his rice paddies. His initial apprehension melts into awe as his productivity soars, highlighting the transcendent nature of innovation beyond cultural boundaries.

1950s-1960s: The Rise of the Combine Harvester

While the reaper had its day, the rise of larger, more powerful combines marked a new era. Their increased capacity and versatility made them the preferred choice for large-scale farming, leading to a gradual decline in reaper use. However, the reaper’s legacy lived on as a stepping stone towards agricultural efficiency.

Short Story:

Picture an aging farmer, reminiscing about his days with the trusty reaper. He acknowledges the efficiency of the combine but cherishes the simpler times and the ingenuity embodied in the reaper, a testament to the enduring impact of even surpassed technologies.

Today: The Reaper’s Legacy in Developing Countries

The reaper’s story isn’t over. While less common in developed nations, it remains a valuable tool in developing countries where manual labor is prevalent and cost-effectiveness is crucial. Its simplicity and reliability continue to serve small-scale farmers, ensuring its place in the global agricultural landscape.

Cyrus McCormick’s invention of the reaper not only revolutionized agriculture but also paved the way for subsequent innovations in farming machinery. The reaper’s enduring legacy is a testament to its impact on global agriculture and the continued relevance of this historic invention in various parts of the world.

The Reaper, more than just a mechanical marvel, was a revolutionary force that forever altered the landscape of agriculture. Its impact went far beyond neatly cut fields, rippling through economies, societies, and even the very fabric of human history. Let’s delve into the multifaceted impact of this ingenious machine:

A Quantum Leap in Productivity:

Prior to the reaper, harvesting was a laborious, time-consuming process, often requiring large numbers of workers. The reaper, with its unmatched efficiency, multiplied individual output by a staggering 50-fold. This productivity boom transformed agriculture from a subsistence activity to a commercial enterprise, fueling economic growth and food security.

Real-Life Story:

Imagine Sarah, a farmer in 1830s Kansas, struggling to harvest her wheat by hand. Each day brought aching muscles and meager yields. Then, a neighbor introduces her to the reaper. Sarah witnesses, with awe, as the machine effortlessly cuts acres in a single day, leaving her with more time and surplus to sell, forever changing her life and livelihood.

Labor Liberation and Social Upheaval:

The reaper’s efficiency had a profound social impact. It freed up labor, leading to mass migration from rural areas to cities, fueling industrialization and urbanization. However, this shift wasn’t without its challenges. Displaced farmworkers faced hardship, highlighting the need for social safety nets during periods of technological disruption.

Real-Life Story:

John, a young farmer in Pennsylvania, initially saw the reaper as a threat to his livelihood. He joined protests against the machine, fearing unemployment. However, as farms adopted the reaper, John saw his opportunity. He trained as a mechanic, servicing and repairing reapers, becoming a vital part of the new agricultural ecosystem.

Geographical Expansion and Global Food Security:

The reaper wasn’t confined to specific crops or regions. Its adaptability allowed it to conquer vast wheat fields in the American Midwest, rice paddies in Asia, and diverse landscapes across the globe. This increased food production contributed significantly to global food security, nourishing growing populations and mitigating famines.

Real-Life Story:

In 1870s Japan, the Tokugawa shogunate faced food shortages. The introduction of the reaper, initially met with resistance, proved instrumental in boosting rice production. Farmers like Hanako, initially skeptical, embraced the machine, ensuring food security for their communities and demonstrating the reaper’s global impact.

Beyond Efficiency: The Reaper’s Legacy:

The reaper’s impact transcended mere productivity. It symbolized the rise of mechanization, paving the way for further technological advancements in agriculture. It also highlighted the importance of innovation in addressing human challenges and sparked debates about the social implications of technological progress.

FAQ

Who invented the mechanical reaper and when?

The mechanical reaper was invented by Cyrus McCormick in 1831. His design revolutionized farming by automating the cutting of grain, which was previously done entirely by hand using sickles or scythes.

What problem did the mechanical reaper solve for farmers?

Before its invention, harvesting crops was extremely labor-intensive and time-consuming. The reaper allowed farmers to harvest fields much faster with fewer workers, saving both time and labor costs

How did the mechanical reaper change food production?

By speeding up harvesting, the reaper enabled farmers to cultivate much larger plots of land. This led to higher crop yields, reduced food shortages, and helped feed rapidly growing populations during the 19th century

What was the economic impact of the mechanical reaper?

The reaper lowered labor costs and boosted productivity, allowing farmers to generate more profit. It also fueled the growth of agribusiness and contributed to America’s rise as a global agricultural powerhouse.

Did the mechanical reaper influence migration and settlement?

Yes. With easier harvesting, farmers expanded westward across the United States. The reaper made large-scale farming on the Great Plains practical, supporting settlement in previously underutilized lands.

How did the mechanical reaper affect farm labor?

While it reduced the demand for manual harvesting labor, it created new roles in machine operation, repair, and manufacturing. This shift marked the beginning of mechanized agriculture and the decline of traditional hand-harvesting methods.

What role did the mechanical reaper play in global agriculture?

The success of McCormick’s reaper spread beyond the United States, influencing farming practices in Europe and other parts of the world. It set the stage for future mechanized tools that transformed global food systems.

How is the legacy of the mechanical reaper seen in modern farming equipment?

Modern combine harvesters are direct descendants of the reaper, integrating cutting, threshing, and processing into a single machine. The mechanical reaper was the foundation of today’s highly efficient mechanized farming.

Conclusion

As we conclude our exploration of the reaper’s remarkable journey, it’s not just a machine we leave behind, but a powerful reminder of humanity’s potential for innovation and progress. From its humble beginnings as a spark in McCormick’s mind to its global impact on agricultural practices, the reaper’s story resonates with themes that transcend time and technology.

A Catalyst for Change: The reaper wasn’t just a harvesting machine; it was a catalyst for social and economic change. It freed up labor, increased agricultural productivity, and fueled the rise of industrial farming. Its impact extended beyond fields, shaping communities, economies, and even the course of history.

Ingenuity Rooted in Need: The reaper’s story reminds us that innovation often blossoms from addressing real-world needs. Inventors like McCormick weren’t driven by abstract ambitions but by a desire to ease the burdens of their communities. This human-centric approach to technology holds valuable lessons for our own age of rapid advancement.

A Testament to Collaboration: The reaper’s success wasn’t just the work of a single inventor; it was a testament to collaboration. From blacksmiths crafting components to farmers providing feedback, countless individuals played their part. This spirit of collaboration serves as a reminder that even the most groundbreaking ideas often flourish through collective effort.

Not an Ending, but a Transformation: The reaper’s decline might seem like an ending, but it’s more accurate to view it as a transformation. It paved the way for more sophisticated combines, ensuring ever-increasing efficiency in food production. The reaper’s legacy lives on, not just in dusty museums, but in the very machinery that continues to nourish our world.

You May also like:

.png)

Nice and informative

Pingback: Cyrus McCormick patented the reaper for the cultivation of grain - Design History Today