Introduction- The Invention of Steamboat

Forget the colossal cruise ships and towering freighters of our modern era. Step back in time, if you will, and envision churning waves kissed by wisps of coal smoke, the rhythmic thump of a hidden engine reverberating through the sturdy wooden hull. This wasn’t just a scene from a historical novel; it was the dawn of a revolution – the invention of steamboat, a vessel unlike any before, etching its mark on the 19th century.

The steamboat’s history wasn’t a dramatic, singular event like the ill-fated Titanic. Instead, it emerged gradually, with whispers of innovation accumulating over decades. Ingenious tinkerers in France, and relentless Scotsmen on the Clyde – each played a role in weaving this tapestry of ambition, frustration, and ultimately, triumph.

Beyond the iconic image of the paddleboat churning the water, fascinating stories lie hidden. Rivalries flared between advocates of churning paddles and sleek propellers, each vying for dominance on the watery stage. Did you know that some early steamboats were opulent floating palaces, their decks adorned with grand dining halls and echoing with the clinking of champagne flutes in bustling gambling dens?

Prepare to delve into the lesser-known chapters from the history of steamboat, where engineering feats intertwined with surprising societal impacts. Whether you’re a history buff yearning for forgotten narratives, an engineering enthusiast fascinated by innovation’s early whispers, or simply captivated by the allure of a bygone era, welcome aboard!

We’ll navigate the winding currents of the steamboat’s invention, uncovering its unique quirks, hidden battles, and the profound mark it left on the world. So, buckle up, dear reader, for this is more than just a history lesson – it’s an adventure into the soul of a groundbreaking invention that changed the course of humanity.

Who Invented the Steamboat?

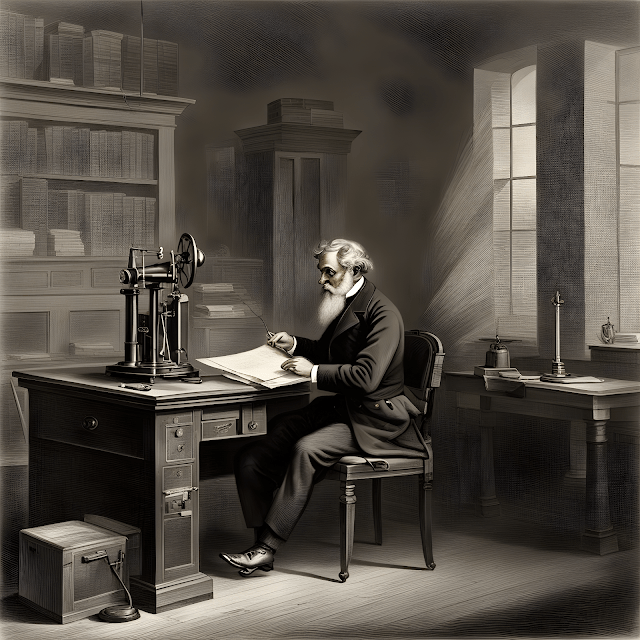

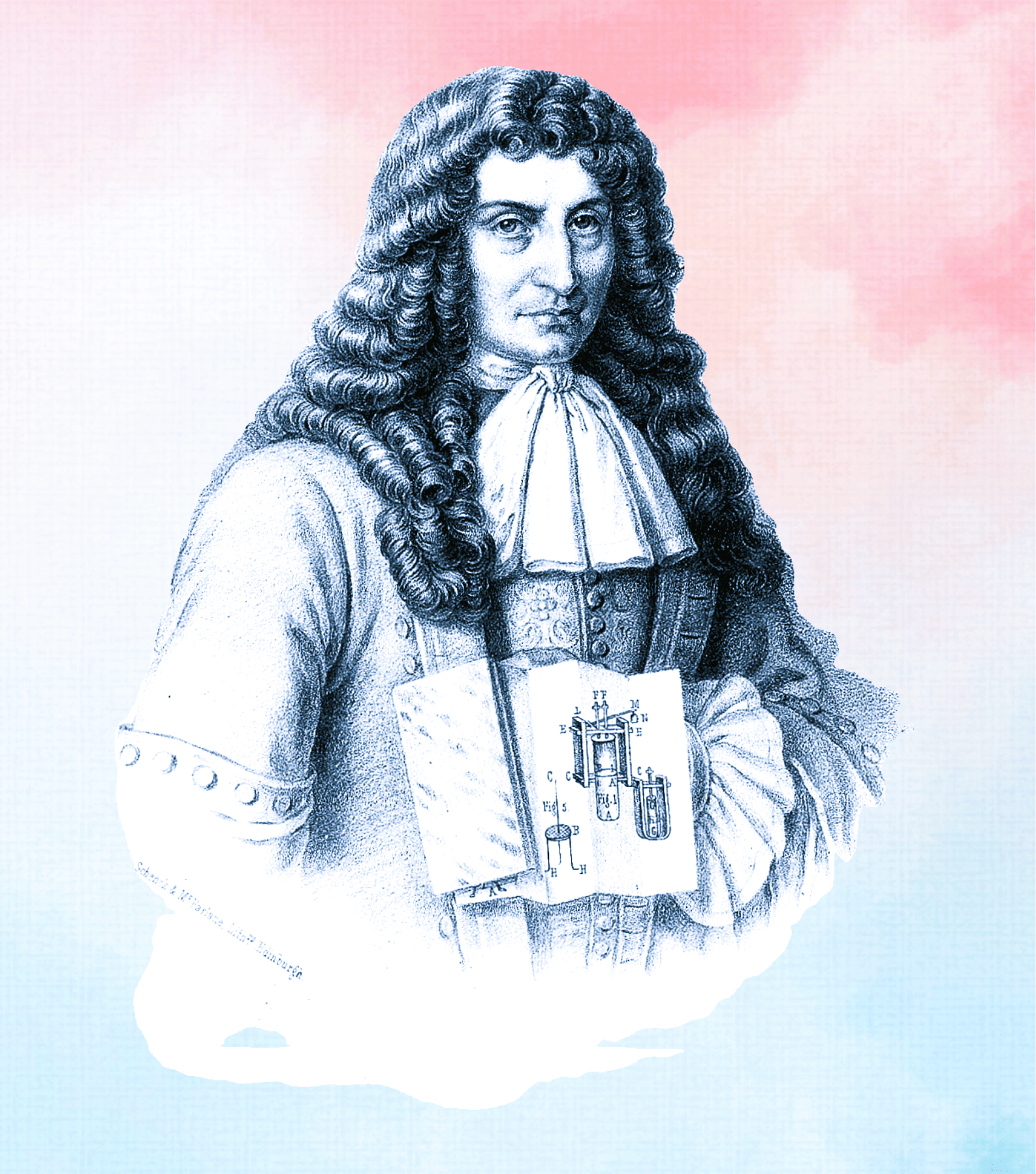

The first steamboat was built by French inventor Denis Papin in the 17th century and steamships in the 1800s started to be widely used for transportation. Papin has made many innovations in steam power and also invented pressure cookers and steam digesters. In 1807 American inventor Robert Fulton built the first commercially successful steamboat named Clermont.

The Clermont was a 133-foot-long vessel with 60 passenger capacity and traveled at a speed of 5 miles per hour. It traveled in the Hudson River from New York City to Albany covering a distance of 150 miles in 32 hours. This was a great achievement over the previous travel time of four days by sailboat

After the success of the Clermont, other inventors and engineers like Robert L. Stevens and John Stevens started contributing improvements of the design of the steamboat. The paddle-wheel steamboat was the most common type of boat which featured two large paddles on either side of the boat. By the mid-19th century, People had started using paddle-wheel steamboats for transportation and business on rivers and lakes throughout the world.

In the 20th century, steamboat technology began to decline as steamships had to carry more load in the form of fuel (Coal) and by this time diesel engines started becoming famous. However, steamboats remained popular for recreational use, with many people enjoying steamboat rides and cruises on rivers and lakes.

Mississippi Riverboat is one of the most famous in steamboat history, which became a symbol of American culture and entertainment. Mississippi Riverboats were often decorated with ornate architecture and luxurious furnishings and featured onboard entertainment facilities such as music, gambling, and dancing. These riverboats became an important part of American folklore and culture.

Timeline of Steam History

17th Century:

The year is 1679, and a quiet hum echoes across the workshop of French inventor Denis Papin. But this wasn’t your average tinkering session. Papin, renowned for his pressure cooker and steam digester, was on the cusp of something revolutionary – a vessel propelled by the very force that cooked his meals. This experimental steamboat wasn’t a roaring behemoth, but rather a modest wooden craft driven by a steam-powered piston. It may not have conquered rivers, but it marked a crucial step in the journey towards steam-powered navigation.

While details surrounding Papin’s steamboat remain hazy, historical references suggest it utilized a paddle wheel driven by a cylinder and piston arrangement. This design echoed his earlier work with steam digesters, where the pressure-driven piston had sparked his imagination. This wasn’t just an isolated experiment; it was a culmination of years spent studying thermodynamics, mechanics, and the potential of harnessing steam’s power.

From Pressure Cookers to Pioneering Spirit:

Papin’s journey wasn’t confined to his workshop. He collaborated with renowned scientists like Christiaan Huygens and Robert Boyle, delving deeper into the mysteries of steam and pressure. While financial constraints and competing priorities prevented him from fully realizing his steamboat vision, his legacy transcended his single invention. His contributions to understanding steam’s principles paved the way for future pioneers like Thomas Newcomen and James Watt, whose innovations ultimately propelled steamboats onto the global stage.

But wait, there’s more! Beyond the technical specifications:

- Did you know Papin’s steamboat faced ridicule and even destruction in his own time? Some feared the dangers of his “fire ship,” highlighting the social resistance early innovators often faced.

- Recent studies suggest Papin might have drawn inspiration from ancient Greek texts describing steam-powered devices, showcasing the fascinating cross-pollination of ideas across centuries.

- While Papin’s steamboat never took to the open waters, its legacy lives on in modern vessels. The iconic whistle of a steam locomotive echoes the pioneering spirit of this inventive mind.

18th Century:

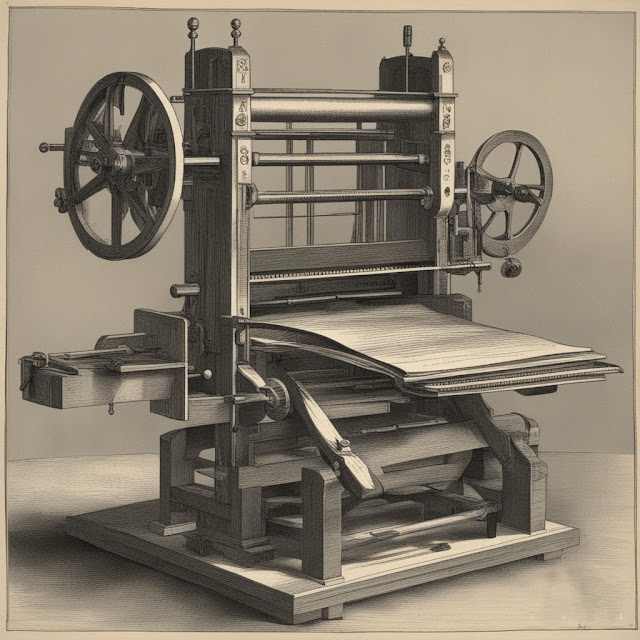

Forget the iconic paddleboats and sleek propellers of later years. In 1736, the vision of a steam-powered vessel was still a mere whisper on the wind. Yet, amidst the bustling workshops of England, a man named Jonathan Hulls dared to dream, securing a patent for a revolutionary design: a boat propelled by the raw power of steam.

Hulls’ patent, while never translated into a functional vessel, marked a pivotal moment in maritime history. It wasn’t just a technical blueprint; it was a seed planted in the fertile ground of human ingenuity. Though Hulls himself faced financial limitations and technical hurdles, his vision resonated with others.

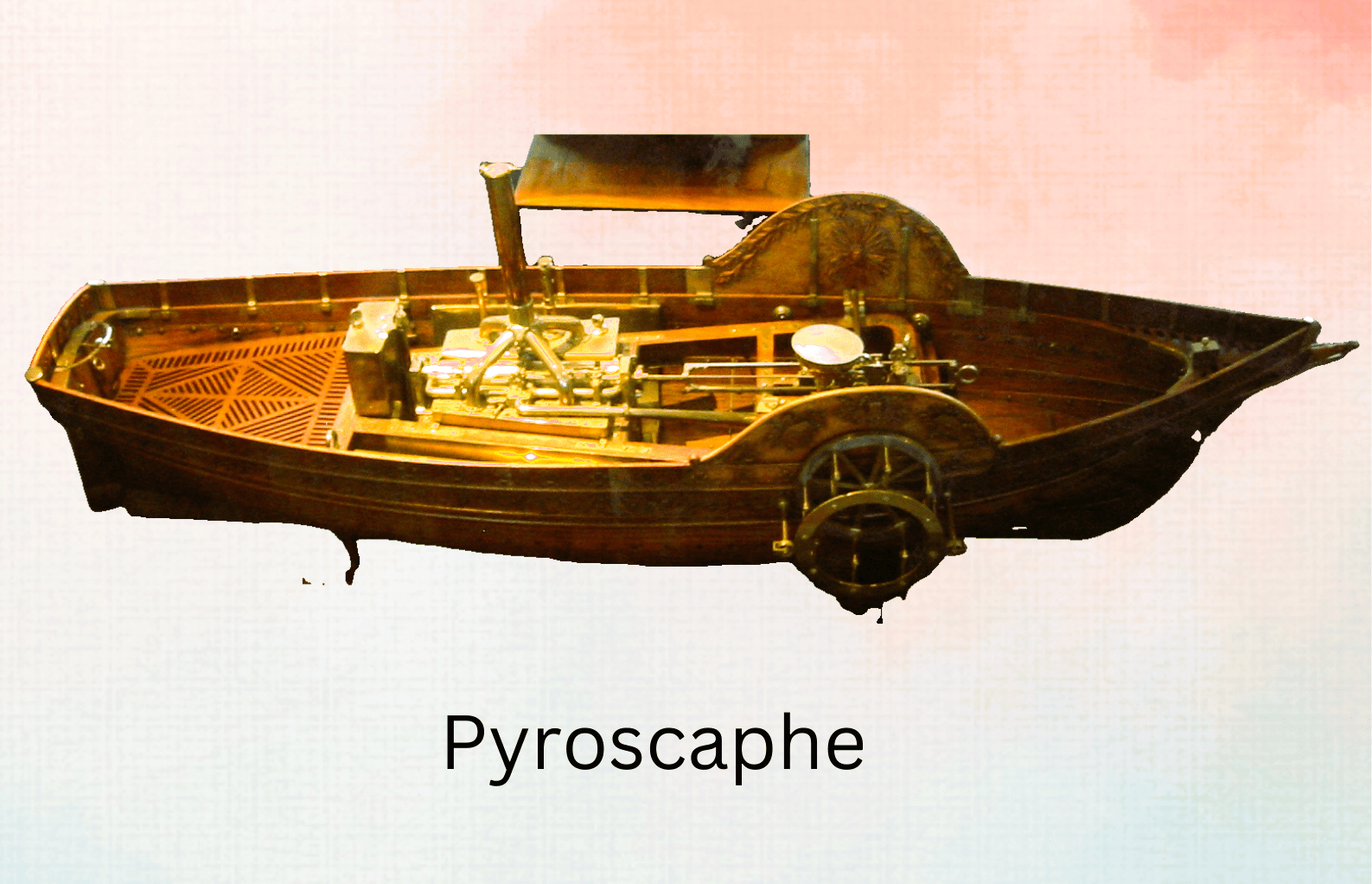

Across the English Channel, in France, a young Marquis named Claude de Jouffroy d’Abbans was captivated by the idea. He devoured Hulls’ patent, fueled by his own ambition to conquer the mighty Rhône River. Years of experimentation followed, culminating in the launch of the “Pyroscaphe” in 1783. This rudimentary vessel, powered by a steam engine and paddle wheels, marked the first recorded instance of a steam-powered boat actually navigating open water. Although short-lived due to technical limitations, the “Pyroscaphe” ignited a spark across Europe, proving the concept’s feasibility.

Meanwhile, in America, a young inventor named James Rumsey dreamt of propelling boats with steam. He conducted extensive studies on steam power, even presenting his findings to none other than George Washington. While Rumsey’s early attempts were met with mixed success, his relentless pursuit of the technology paved the way for future American inventors like Robert Fulton.

Beyond the technical details, the story of Hulls’ patent and its ripple effects is rich with fascinating anecdotes:

- Hulls’ inspiration: Some historians believe he drew inspiration from observing the movement of steam-powered bellows in blacksmith shops.

- The “Pyroscaphe’s” trials: The boat’s maiden voyage was met with public skepticism, with some spectators even throwing stones at it!

- Rumsey’s demonstrations: He famously showcased his steam-powered model boat on the Potomac River, impressing even Benjamin Franklin.

These early attempts, though not immediately successful, laid the groundwork for the steamboat revolution that would transform the world.

Late 18th Century:

1765: Long before Fitch’s paddle-churning marvel, a shadowy figure named Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot in France ignites the spark. His “fardier à vapeur,” a clunky three-wheeled contraption powered by steam, sputters along a road near Paris, marking the first recorded steam-powered land vehicle. Though not technically a boat, it whispers the potential of steam to revolutionize transportation.

1778: Across the Atlantic, the indefatigable James Rumsey, an American inventor and blacksmith, makes waves on the Potomac River with his steam-powered boat. His design, employing a jet propulsion system, sparks fierce competition with Fitch, setting the stage for a race to perfect the steamboat.

1783: Enter John Fitch, a fiery entrepreneur fueled by a vision of steam-powered transportation. Obsessed with a dream of canoes chasing him, he embarks on a decade-long journey, meticulously testing and refining his steamboat designs. His early prototypes, powered by oars driven by a steam engine, might seem comical, but they lay the groundwork for future innovations.

1787: The moment arrives! On the Delaware River, Fitch unveils his 45-foot masterpiece, propelled by a bank of oars driven by a steam engine. This wasn’t just a test run; it was a public spectacle, witnessed by delegates to the Constitutional Convention. The chugging boat, defying the current, captured the imagination of a nation and cemented Fitch’s place as a pioneer in steam navigation.

Beyond the Dates:

- Fitch’s struggles: While Fitch’s success was undeniable, his journey wasn’t smooth sailing. Financial woes, fierce competition from Rumsey, and public skepticism plagued him. He even faced accusations of stealing Rumsey’s ideas, highlighting the intense rivalry driving this innovation.

- The paddle vs. propeller debate: Fitch’s oars wouldn’t rule the waves forever. Soon, the battle between paddle and propeller propulsion heated up. Early advocates for propellers included the visionary David Rumsey, whose son, James, continued his father’s legacy.

- The “Perseverance” and its legacy: Though overshadowed by later inventions, Fitch’s “Perseverance” deserves its place in history. It wasn’t just a boat; it was a symbol of American ingenuity and the dawn of a new era in transportation.

Early 19th Century:

-

1807: While Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston’s Clermont is rightfully celebrated, whispers of steamboats echoed earlier. In 1783, Frenchman Claude Jouffroy navigated the Saône River, and James Rumsey trialed a steamboat on the Potomac in 1789. Fulton, however, combined existing innovations, securing financial backing and creating a commercially viable vessel. His journey wasn’t smooth sailing; skeptics mocked the “Fulton’s Folly,” but the Clermont’s 32-hour trip proved them wrong.

Fulton’s Innovation:

Fulton, building upon these earlier efforts, incorporated several key elements to create Clermont’s success:

- Improved Engine: He utilized a more powerful and efficient steam engine designed by William Symington.

- Paddlewheel Design: He adopted a robust paddlewheel system inspired by Rumsey’s design.

- Financial Backing: Livingston, a wealthy diplomat, provided crucial financial support and political connections.

Beyond the Celebration:

Despite its success, the Clermont’s journey wasn’t without challenges:

- Skepticism and Ridicule: The “Fulton’s Folly” moniker highlighted public skepticism towards this new technology.

- Legal Battles: Rumsey’s prior patents led to legal disputes that delayed Clermont’s commercial launch.

- Limited Range: The Clermont’s early voyages were short, highlighting the need for further engine improvements.

Historical References:

- “A Short History of Steam Navigation” by Arthur C. Wardle provides a detailed account of early steamboat development.

- “The Steamboat Era” by Louis C. Hunter explores the social and economic impact of steamboats in the United States.

- “The Clermont: The Birth of the Steamboat” by John F. Baker delves into the specific details of the Clermont’s construction and journey.

1811: The New Orleans: Nicholas Roosevelt, not Robert Fulton as often assumed, deserves credit for this pioneering vessel. The New Orleans wasn’t just “designed,” it was engineered for the Mississippi’s unique challenges. Its shallow draft and powerful engines, fueled by locally sourced wood, allowed it to navigate the river’s shifting currents and sandbars, unlike Fulton’s earlier designs.

Beyond the Maiden Voyage: While the New Orleans’ initial trip from Pittsburgh to New Orleans took a grueling 45 days, it proved the concept’s viability. Soon, steamboats were transforming the Mississippi Valley:

- Trade Boosted: Cotton, corn, and other goods flowed faster and cheaper, fueling the region’s economic growth. Towns like Memphis and St. Louis boomed as trade hubs.

- Westward Expansion: Steamboats transported settlers, soldiers, and supplies, facilitating westward expansion and opening up new territories.

- Cultural Exchange: Passengers from diverse backgrounds mingled onboard, fostering cultural exchange and influencing music, food, and storytelling along the river.

Lesser-Known Facts:

- The “Green Monster”: The New Orleans’ nickname derived from its use of green wood, readily available but requiring frequent refueling stops.

- Pirate Problems: River pirates targeted steamboats, leading to armed guards and gunfights on the Mississippi.

- Slavery’s Stain: Sadly, steamboats also facilitated the transportation of enslaved people, highlighting the complex and often dark realities of this era.

Different Perspectives:

- Native Americans: The steamboat’s arrival disrupted their traditional way of life, displacing communities and altering river ecosystems.

- Women: While some women found opportunities on steamboats as cooks or entertainers, others faced discrimination and exploitation.

- Working Class: The grueling labor of stokers and deckhands contrasted with the opulence enjoyed by first-class passengers.

Beyond the Mississippi:

- The New Orleans’ success inspired the development of steamboats for other rivers like the Ohio and Missouri, creating a vast network of inland waterways.

- The technology also spread globally, impacting trade and exploration on rivers like the Nile, Amazon, and Danube.

Historical References:

-

-

- Walter Havighurst’s “The River” provides a captivating narrative of the Mississippi and its steamboats.

- Mark Twain’s “Life on the Mississippi” offers a humorous and insightful perspective from a steamboat pilot.

- The National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium in Dubuque, Iowa, houses artifacts and exhibits showcasing the impact of steamboats.

-

1824:

While the SS Savannah’s 1824 transatlantic voyage under steam and sail holds its place in history, its story is far richer than a simple “first.” Let’s delve deeper, unearthing lesser-known facts and historical references that paint a more nuanced picture of this groundbreaking vessel.

A Hybrid Pioneer:

-

Unlike most “steamboats,” the Savannah wasn’t built solely for steam propulsion. Originally planned as a sailing ship, it was retrofitted with a side-mounted steam engine and paddle wheels, making it a true hybrid. This unique design reflected the early days of steam navigation, where caution and practicality often trumped pure innovation.

-

The engine itself was a marvel of American ingenuity, designed by Stephen Vail of Morristown, New Jersey. Interestingly, it was fueled by a mix of coal and wood, highlighting the limitations of early coal-fired technology.

A Journey of Skepticism and Wonder:

-

The Savannah’s 27-day voyage was far from smooth sailing. The engine, intended for calm seas, proved unreliable in rough weather, forcing reliance on sails for much of the journey. This fueled skepticism about the viability of steam for long-distance travel.

-

Despite the challenges, the Savannah’s arrival in Liverpool caused a sensation. Crowds marveled at the “fire-breathing ship,” newspapers hailed it as a harbinger of a new era, and King George IV himself granted the crew an audience.

Beyond the Headlines:

-

The Savannah’s story doesn’t end with its arrival in England. It returned to the US, but its hybrid design proved commercially impractical. The engine was dismantled, and the ship reverted to its original purpose as a sailing vessel. Tragically, it was wrecked off the coast of Long Island in 1821.

-

Interestingly, the Savannah also carried the first American-built locomotive, the “Best Friend of Charleston,” on its transatlantic journey, further highlighting the burgeoning era of a transportation revolution.

A Legacy of Innovation and Inspiration:

-

While not a commercial success, Savannah’s voyage proved the feasibility of transatlantic steam navigation. It paved the way for future steamships like the SS Great Western, which achieved sustained steam propulsion across the Atlantic just five years later.

-

Savannah’s story reminds us that innovation rarely follows a straight path. It’s often a blend of ambition, practicality, and even a touch of luck that leads to breakthroughs.

Further Exploration:

-

For a deeper dive, explore the book “The Savannah” by William C. Davis, which delves into the ship’s design, construction, and voyage.

-

Visit the Georgia Historical Society’s website to learn more about Savannah’s history and its impact on the state.

Mid-19th Century:

1838: The SS Great Western wasn’t just a leviathan on the Atlantic, it was a political statement. Its fast crossing proved Britain’s maritime dominance, sparking a fierce rivalry with American lines like Cunard. Interestingly, the ship’s paddle-wheel design was deemed inefficient by critics, foreshadowing the rise of propellers.

1840s: While paddle-wheelers dominated rivers, a quieter revolution brewed beneath the waves. Francis Pettit Smith’s Archimedes in 1845 proved the propeller’s efficiency, leading to its adoption by the Royal Navy and Cunard in 1843. This wasn’t just a technological shift; it was a cultural one. Propellers were quieter, allowing passengers to enjoy the sounds of the sea instead of the thrumming of paddles.

Beyond Paddle vs. Propeller:

-

Iron vs. Wood: The mid-19th century saw a shift from wooden to iron hulls. Pioneering ships like the SS Great Britain (1843) were marvels of iron construction, offering greater strength and fire resistance. This innovation allowed for larger ships and longer voyages, pushing the boundaries of transatlantic travel.

-

The California Gold Rush: Steamboats played a crucial role in the Gold Rush of 1848. Paddle-wheelers like the SS California transported eager prospectors up the Sacramento River, fueling the boom and transforming California into a bustling state. Interestingly, steamboats also faced competition from camel caravans across the desert, highlighting the diverse modes of transportation in the era.

-

River Rivalries: While transatlantic routes witnessed national rivalries, river systems within America had their own colorful competitions. The Mississippi saw fierce competition between rival lines, advertising speed, luxury, and entertainment to attract passengers and cargo. One such rivalry between J.M. White and Robert E. Lee led to tragic consequences – the infamous “Race of 1870,” resulting in a boiler explosion and loss of life.

-

Steamboat Disasters: Despite their transformative impact, steamboats were not without dangers. Boiler explosions, fires, and groundings were tragically common. The most infamous disaster, the Sultana explosion in 1865, claimed over 1,700 lives, making it the deadliest maritime disaster in American history.

Late 19th Century:

The 1870s weren’t just about the compound steam engine. While this innovation, featuring multiple cylinders and expanding steam in stages, boosted efficiency by 20-30%, it was part of a wider technological surge. Steel hulls replaced iron, offering greater strength and allowing for larger vessels. Additionally, surface condensers improved fuel consumption, and forced draft boilers increased power output. These advancements weren’t just technical marvels; they fueled global trade and exploration.

Beyond the Transatlantic:

-

African Odyssey: In 1874, David Livingstone, famed explorer, utilized the steamship Lady Nyassa on Lake Malawi, highlighting the role of steamboats in opening up Africa’s interior.

-

Nile Navigation: The Khedive Ismail of Egypt, aiming to modernize his nation, invested heavily in steamships for the Nile. By 1898, over 400 steamers plied the waterway, facilitating trade and travel.

Speed Demons & The Blue Riband:

The late 19th century saw fierce competition for the prestigious Blue Riband, awarded to the fastest transatlantic crossing.

- 1882: The British Servia claimed the title with a 7.82-knot average speed, showcasing advancements in propeller design and hull streamlining.

- 1885: The German Eider challenged with a 8.6 knots average, demonstrating the rise of continental rivals.

- 1893: The American City of New York shattered records with a 20.19-knot average, fueled by quadruple-expansion engines and innovative hull design. This reignited American dominance and pushed the boundaries of speed and luxury.

Beyond Passenger Liners:

While iconic vessels like the RMS Oceanic captured the public imagination, cargo ships underwent a quiet revolution. Steam-powered freighters revolutionized trade, transporting bulk goods like coal, grain, and oil across vast distances. These workhorses of the sea, often overlooked in history, laid the foundation for modern global trade.

Lesser-Known Stories:

- Icebreakers: As exploration pushed into arctic regions, innovative icebreakers like the Yermak (Russia) and Fram (Norway) used powerful steam engines and reinforced hulls to forge paths through frozen seas.

- Riverboats of the Amazon: Smaller steamboats navigated the Amazon’s treacherous tributaries, opening up the rainforest for resource extraction and exploration. These vessels, often built locally, faced unique challenges and played a crucial role in shaping the region’s history.

20th Century:

1900s:

While the 20th century saw the decline of steam power in commercial shipping, it was far from a simple sunset. This era was marked by innovation, adaptation, and a surprising resurgence of steam in unexpected corners. Let’s delve deeper:

Diesel’s Rise, Steam’s Resilience (1900s):

-

Diesel’s Early Challenges: While your statement about diesel’s advantages is accurate, it’s important to note that early diesel engines were unreliable and prone to breakdowns. Steam remained dominant for decades, especially in passenger liners where comfort and reliability were paramount.

-

The “Heavy Oil Revolution”: By the 1930s, advancements like direct fuel injection and improved metallurgy made diesel engines more reliable and efficient. The “Heavy Oil Revolution” saw diesel replacing steam in cargo ships, tankers, and even warships.

-

Steam’s Last Stand: However, steam wasn’t entirely vanquished. Passenger liners like the iconic Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth continued to rely on steam turbines for their speed and smooth operation. Steam also persisted in niche roles like harbor tugs and ferries, valued for their maneuverability and low emissions.

Beyond the Commercial:

-

Military Might: While diesel dominated the seas, steam remained crucial in naval warfare. Steam turbines powered battleships like the Yamato and Iowa, offering superior speed and firepower until the late 1940s.

-

Riverboats & Showboats: On inland waterways, steamboats continued to thrive. The Mississippi saw paddle-wheelers like the Delta Queen carrying tourists and preserving the romantic allure of the bygone era. Showboats, like the American Duchess, brought entertainment to river towns, becoming cultural icons.

-

Leisure & Luxury: Steam yachts remained a symbol of affluence throughout the century. From J.P. Morgan’s Corsair IV to Aristotle Onassis’ Christina O, these opulent vessels offered unparalleled comfort and personalized service.

Lesser-Known Facts:

-

Nuclear Steam: In the Cold War, the USSR experimented with nuclear-powered icebreakers, like the Lenin, proving steam’s adaptability even in the atomic age.

-

Modern Steamboats: Even today, specialized steamboats operate. The MV Britannia, built in 1973, remains the only coal-fired passenger liner in service, offering a unique and nostalgic experience.

-

Steam’s Legacy: From powering naval giants to charming riverboats, steam’s impact on the 20th century went far beyond mere commercial shipping. It left an indelible mark on culture, technology, and our collective imagination.

Mid-20th Century:

1950s:

The 1950s marked a significant turning point for steamboats. While diesel engines cemented their dominance in commercial shipping, steam wasn’t relegated to the history books. It found new life in surprising corners, proving that even in an age of innovation, nostalgia and unique experiences have enduring value.

The Diesel Dominance: By the 1950s, diesel engines had firmly established themselves as the fuel of choice for commercial vessels. Their advantages were undeniable: lighter weight, reduced fuel consumption, and higher efficiency made them ideal for long-distance cargo and passenger transportation. The iconic Queen Mary completed her final transatlantic voyage in 1967, marking a symbolic end to the era of steam-powered liners.

Steam’s Second Act: Recreational Revival: While seemingly obsolete in commercial terms, steamboats found a new lease on life in the burgeoning leisure industry. The charm of paddle-wheelers, the soothing thrum of the steam engine, and the connection to a bygone era resonated with tourists and enthusiasts.

- Paddlewheel Paradise: The Mississippi River remained a haven for steamboats like the Delta Queen and American Queen. These “floating palaces” offered scenic cruises, authentic dining experiences, and a chance to relive the golden age of river travel.

- Showboats Delight: Showboats continued to ply the waterways, bringing live entertainment and theatrical productions to river towns. The American Duchess, meticulously restored and still operational today stands as a testament to the enduring allure of these floating stages.

- Maritime Museums: Historic steamboats found a new role as museum ships, preserving their legacy and educating future generations. The SS Jeremiah O’Brien, a Liberty Ship from World War II, offers educational tours and even sails for special events, keeping the spirit of steam alive.

Beyond Nostalgia: Sustainability & Innovation:

Interestingly, the conversation around steamboats doesn’t end with nostalgia. Recent developments suggest a potential revival in specific applications:

- Biofuel-powered Steam: The MV Britannia, the world’s last coal-fired passenger liner, is exploring the use of biofuels as a cleaner alternative. This could offer a sustainable future for steam-powered tourism.

- Hybrid Designs: Innovative engineers are experimenting with hybrid designs combining steam and electric power, aiming for increased efficiency and reduced emissions.

This timeline shows how the steamboat was developed and improved over several centuries, from the early experimental vessels to the massive ocean liners of the late 19th century. The impact of the steamboat on transportation and commerce was immense, and its legacy continues to be felt today.

The steamboat changed the course of transportation and commerce by transporting goods and people quickly and efficiently along waterways. Before the steamboat, river transportation depended on sailboats and barges, which were slow and dependent on wind and currents. The steamboat made it possible to travel upstream against the current, opening up new areas for

settlement and commerce.

Steamboats had their share of disadvantages and risks despite their many benefits. Boiler explosions aboard steamboats frequently resulted in accidents and fatalities. They were also susceptible to collisions with other vessels, fires, and floods.

Conclusion

From humble puffing vessels to ocean-conquering behemoths, the steamboat’s story isn’t simply a timeline of inventions; it’s a tapestry woven with human ambition, societal shifts, and a touch of smoke-stack romance. The journey wasn’t linear – it was a dance between trial and error, fueled by the dreams of tinkerers and the determination of nations.

Beyond revolutionizing transportation and trade, steamboats opened up frontiers, fueled westward expansion, and became vessels of culture and leisure. They ferried not just cargo and passengers, but also dreams, ambitions, and the very fabric of a burgeoning nation. Their legacy isn’t confined to museums; it echoes in the bustling ports they birthed, the folklore they inspired, and the spirit of innovation they ignited.

Today, as we stand on the shoulders of these maritime giants, it’s crucial to remember their story. It’s a reminder that progress is rarely a solo endeavor and that even the most seemingly obsolete technologies can leave an indelible mark. So, the next time you hear a distant foghorn or see a sleek cruise ship glide by, remember the chugging pioneers that paved the way, their legacy carried on the waves of time.

Check out some of my other blog posts: